Reviews & Articles

Au Hoi Lam: My Father is Over the Ocean

John BATTEN

at 11:52am on 14th August 2013

Captions:

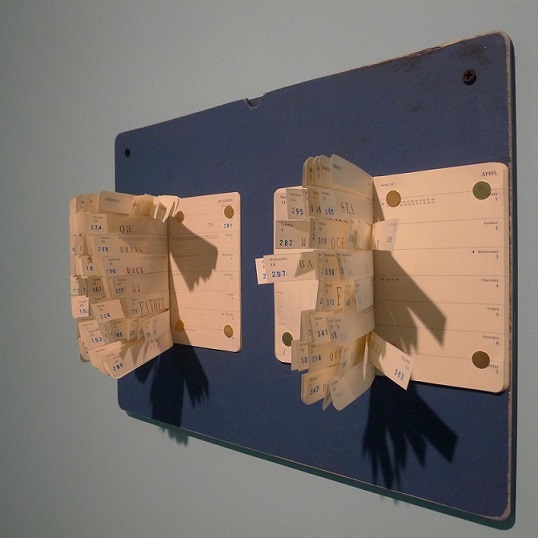

1. Log (2012.03.25 - 2013.03.25), oil-based ink, two weekly diaries, nails, acrylic, wooden drawing board, 30.5 x 40.5 x 10 cm, 2013.

2. 60 Questions for My Father (or For Myself) - detail view, mixed-media installation (using bunk beds), 2012-2013.

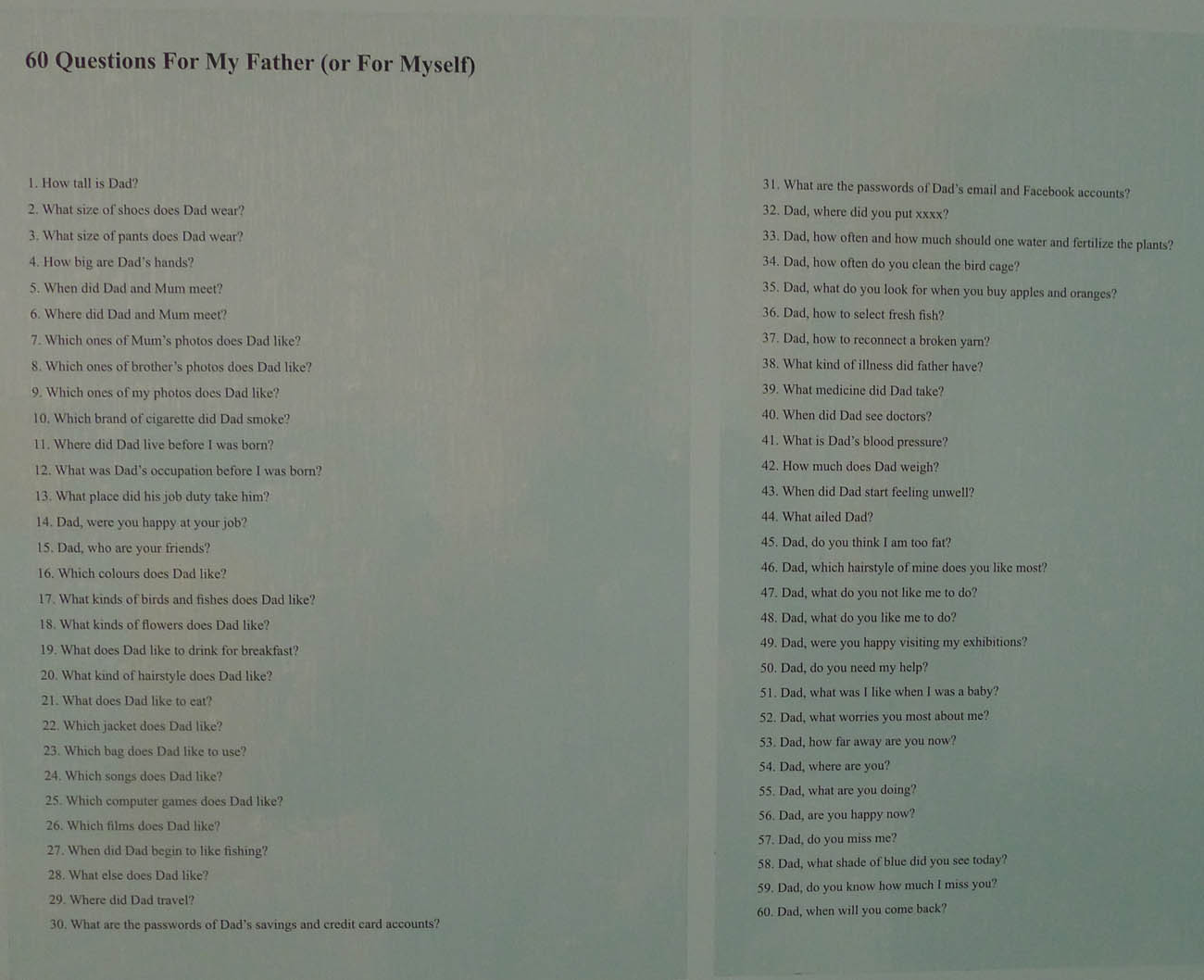

3. Actual list of Au Hoi Lam's 60 questions for my father (or For Myself), exhibition wall signage.

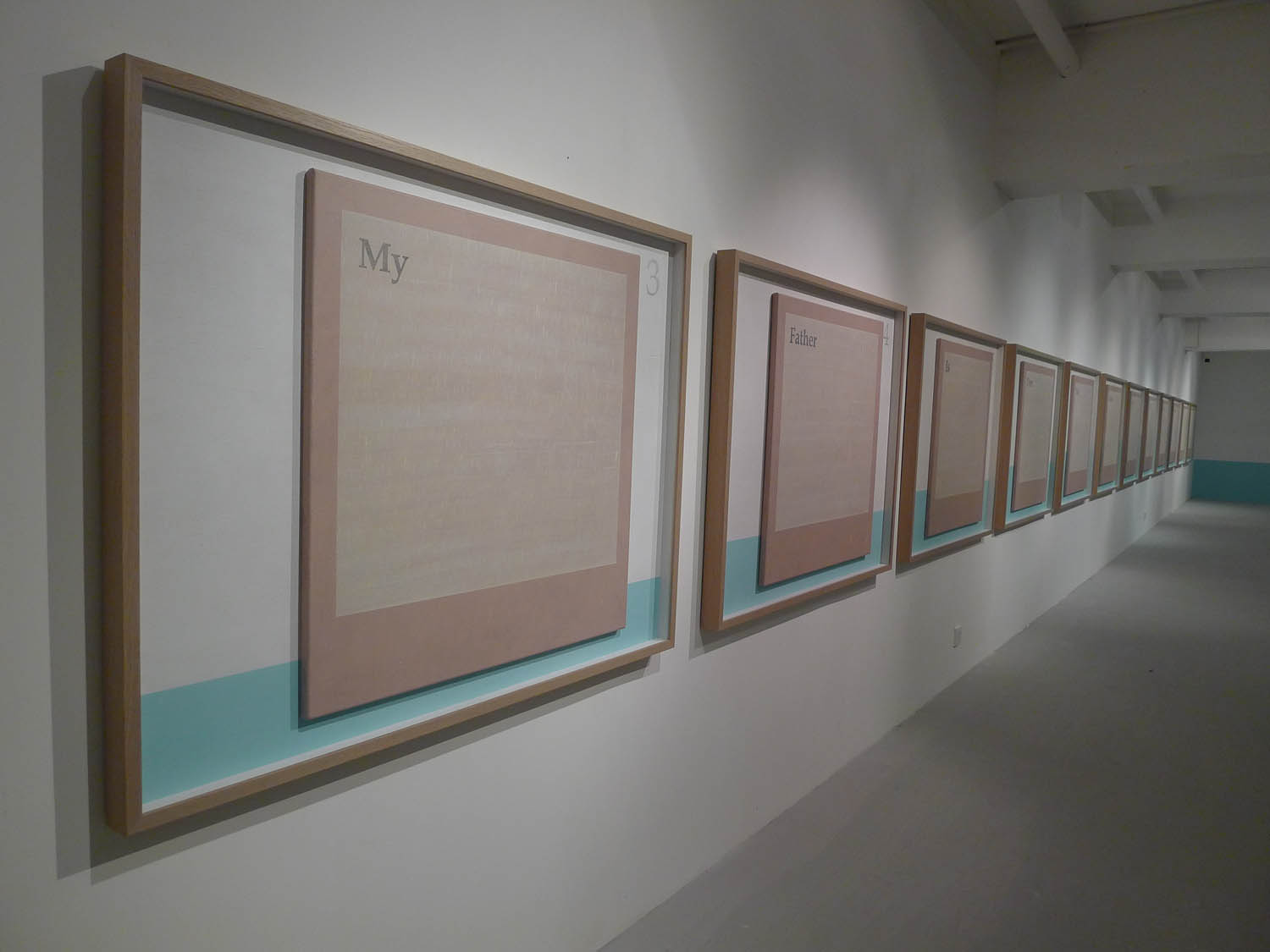

4. There is a Song (Twelve Words Twelve Months Twelve Exercises) - installation view, pencil, acrylic, emulsion paint, linen, wooden board and wooden frame, set of 12 pieces, 96 x 126 x 5.2 cm each, 2012-2013.

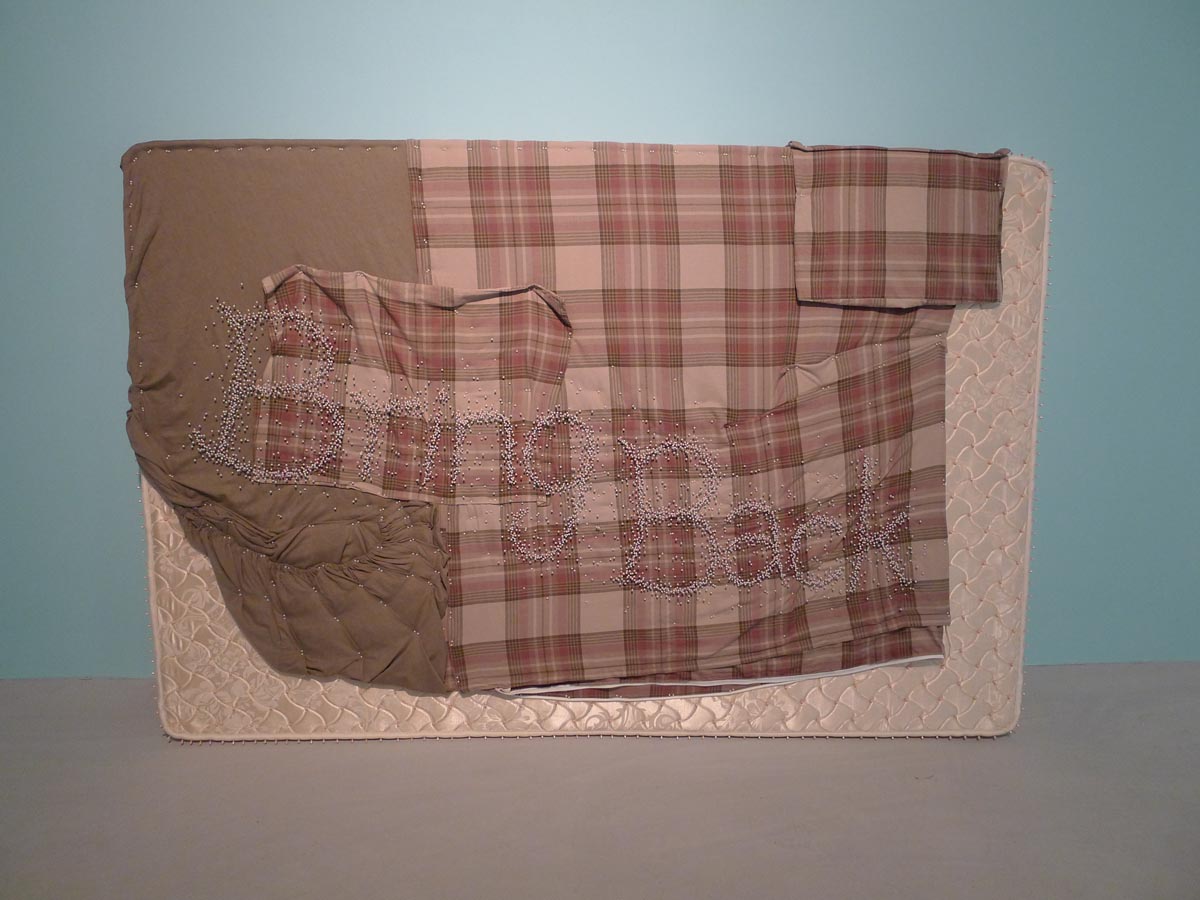

5. There are Some Pearls, pearl head pins, new printed cotton double and single bedding set, felt, used mattresses, 2012-2013.

(原文以英文發表,評論《區凱琳:爸爸出海去》個展。)

Exhibition review:

Au Hoi Lam: My Father is Over the Ocean

by John Batten

Tinged with melancholia and sensitivity, Au Hoi Lam’s exhibition is much gutsier than initial impressions. In fact, it is the most compelling confession in art – of guilt, regret, gratitude and love – seen for years in Hong Kong. It is ostensibly about the recent death and memory of her father, but the layers are murkier:

“My parents met their grand-daughter for the first time. XXXXXXXX. A few days later, my father dismantled my old bed and put it away. He bought a new set of bunk beds which could sleep three persons. He said that we could use the beds whenever we came home for visits. XXXXXXXX”

In Bunk Beds & Boat, memories are carefully typed, consciously exposing text while other sections are deliberately erased out (noted by the ‘X’ above). Truths are revealed, as is the suggestion of previous “lies”.

In Elsewhere (2011), her previous exhibition, Au quietly revealed the inspiration of much of her art over the last decade: her daughter. A much-loved child born secretly and unknown by friends; and, principally cared for in those intervening years by Au’s parents. This public ‘coming out’ and the emotion of the truth embroiled with her father’s sickness makes 'My Father is Over the Ocean' a compelling bridge between the artist’s past, often opaque work, and her future.

Her father’s bunk beds dominate the exhibition in the installation Sixty Questions for My Father (or For Myself). The disassembled bed both references a peripatetic normalcy of home-life for Au’s daughter and her father’s final resting place. The bed’s wooden panels and support slats are spread around the gallery and written on asking sixty mundane but fundamental questions in appreciating a missed father: “How big are Dad’s hands?”, “Dad, what was I like when I was a baby?” etc. His mattress, with the words ‘bring back’ etched in arranged pearl-headed sewing pins, sits alongside brown-coloured (overtly male) tartan bed sheeting.

Au’s father was a customs officer and spent time at sea. The exhibition’s leitmotif is embodied in the artist’s slowly sung dirge, faint child’s lullaby and lament of My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, recorded next to a stream near her Tai Po home. Dates have been significant in Au’s recent work: to obliquely locate the truth when “lies” needed to be maintained. This innocent song, not party to any deception, was recorded exactly nine months after Au’s father’s death. Its poignant repeat echoes a daughter’s longing for a kind, understanding father.

Exhibition:

Au Hoi Lam: My Father is Over the Ocean

Osage Gallery, Kwun Tong, 22 March – 22 April 2013

A version of this review was published in the South China Morning Post, 14 May 2013.