Reviews & Articles

A Review of “Frogtopia. Hongkornucopia” at the Venice Biennale

wen yau

at 4:25pm on 14th October 2011

Captions:

1. Frog King in full froggy costume.

2. Images of Frog King's work in froggy windows.

3. Traces of Frog King's action painting on the wall make a contemplative comparison to the video documentation of his performances, etc.

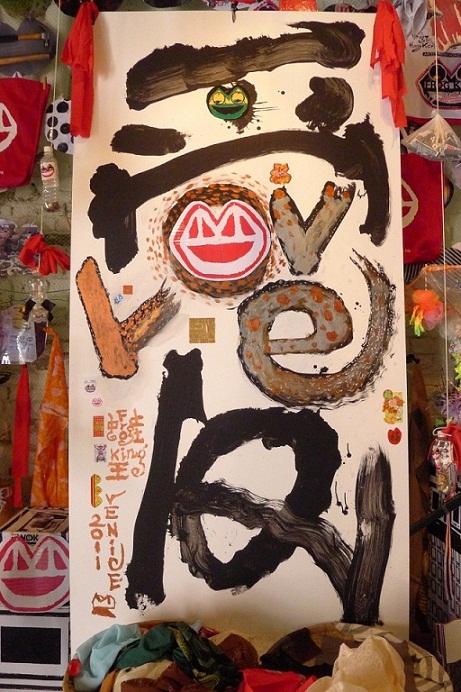

4. Frog King can never stop making art, and this work was produced in Venice during his stay in the Frog Nest (Photo courtesy of Frog King).

5. Frog King was doing calligraphy when visitors came to the pavilion (Photo courtesy of Frog King).

© All photos by wen yau unless specified.

(原文以英文發表,評論第54屆威尼斯雙年展香港館展覽《蛙托邦鴻港浩搞筆鴉》。)

(The website does not allow correct formatting of this document.)

Transcendence of (Im)mortal Life, Disappearance from the Bustling Arena, or Something Else?

A Review of “Frogtopia. Hongkornucopia” at the Venice Biennale

by wen yau

Talking about Frog King has never been an easy thing.

This year, at the 54th Venice Biennale, the Hong Kong pavilion presents veteran artist Kwok Mang-ho (aka Frog King) in an exhibition titled “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia.”

People often have extreme responses to Frog King and his work – some very much enjoy his interventions, happenings and performances, where paper flies everywhere and everybody is making music with plastic bottles, cooking pans and the like; some admire his vibrant creative energies that have kept his artistic career alive for over 40 years; some find his spontaneous, carefree and self-absorbed style and action bedeviling, and some complain that he has just been repeating himself in his work for years and not keeping up with current trends... However, one cannot deny the significance of Frog King as an innovative and pioneering artist in Hong Kong or even China.

Froggism: “Art is Life, Life is Art”

Frog King was the first artist to engage in performance art in Hong Kong and mainland China. In 1975, he dumped a bag of burnt cow bone next to his award-winning sculpture “Fire Sculpture” in the Contemporary Hong Kong Art exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, which organized the annual competition of the same title, and discussed artistic concepts with the audience. As the first documented happening or performance art piece in Hong Kong (1), Frog King’s action challenged institutional power and shifted the power of interpretation to the audience by inviting them to join in active participation. Audience participation pays a significant role in Frog King’s happenings or “Frog-fun-lun” (蛙玩臨) – a term that he adapted from the term “Hark Bun Lum” (客賓臨) he invented for his happenings in the 1970s, literally meaning “arrival of guests”. His fun and joyful performances are often highly attractive and enticing, pulling the audience in to participate.

On the other hand, Frog King studied with Lui Shou-Kwan, the master artist and advocate of the New Ink Painting Movement in Hong Kong during the 60s and onwards. Inspired by Lui, Frog King’s free-style ink painting and calligraphy brought the form and spirit of traditional Chinese art forward into today’s highly westernized cultural context. Distinguished by the abundance of images borrowed from popular culture, his work of collage using ink calligraphy, photos and images from newspapers or magazines illustrates the cosmos of love and harmony that can be found in traditional Chinese ink painting as well – this chaos of images, calligraphy and painting creates a surrealistic atmosphere through multiple perspectives and converges into a universe of wholeness. His recent series of Chinese calligraphy, which blends English into Chinese characters, also demonstrates Frog King’s continuing efforts to experiment with the medium and promote the spirit of Chinese ink painting in the contemporary context. Traces of the Zen and Tao philosophy that are deeply ingrained in traditional Chinese art can also be found throughout Frog King’s oeuvre. Out of the tangible and figurative images, he attempts to extract a kind of spiritual, poetic harmony.

The frog is a recurring motif in Frog King’s oeuvre. His signature or icon in the shape of a frog head with triangular crown or mountain-like eyes and a half-moon-like broad grin is probably the best example. The well-known froggy glasses that he keeps on making are for the project in which he invites people he meets randomly to put on and pose for snapshots. As he puts it, the frog is a kind of flexible and adaptive creature with strong vitality. At the age of 64, Frog King is still active in the local and international art scene. From Hong Kong to New York where he lived for 15 years (1980-1995) during the heyday of avant-garde art, and more recently Korea, Beijing and Shanghai where he has set up studios with his wife Cho Hyun-jae, Frog King leaps around swiftly, not confined by any forms, mediums or cultural differences. Plastic bags, rotten eggs, toilet paper, cloth, bras, paper of all sizes, roast suckling pigs, table-tennis balls or any other gadgets he picks up in everyday life are being used in his performances and installations in any places and at any time. Wherever he dons his layered “froggy” costume, his energy is so contagious that it draws in the audience.

When looking at Frog King’s motto: “Art is life, life is art” (or sometimes “Art is frog, frog is art”), one may think of other renowned artists such as Allan Kaprow, Tehching Hsieh and Marina Abramović. Somehow Frog King follows the cannon of Kaprow’s notion of happenings, which connotes a form of improvisation, fluidity, open-ended-ness, serendipity and impermanence as opposed to conventional theatre (2). Just like Hsieh’s One Year Performances in which the artist confined himself to certain extreme physical living and even existential conditions within a specific period of time, or Abramović’s very long durational pieces that push the boundary of one’s endurance, Frog King’s work is about the artist’s presence, sharing with others at every moment of here and now. Indeed, Frog King is making his creative practice a ritual of everyday life rather than separate component of it, a ritual of spiritual pursuit that purifies himself, his work and the world beyond the material.

Most people would be stunned by the vast amount of materials he keeps in his studio or the “Frog King Kwok Museum” which is a total project in and of itself. His museum houses documentation such as remnants, slides and photos of performances, exhibitions as well as everyday household objects he has collected and assembled for experimentation and exhibition, an abundance of the ink paintings and calligraphy he produced every day and many more things, all stored in a highly compact manner. This is a statement in itself, one that reveals his spatial aesthetics through populating and occupying physical space with his creative spirits. Tsang Tak Ping, one of the curators of this year’s Hong Kong Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, observes, “It forms a paradoxical landscape in which he uses objects and materials he has found to mock as well as transcend the materialistic world”(3). By packing physical spaces with the maximum amount of materials, he is like a martial arts master pushing himself in extreme conditions so as to attain spiritual transformation and advancement ascetically.

“Kwok was an innovator of an avant-garde art movement that no one dared to follow at a time when Hong Kong’s boundaries where defined by ancient tradition with a new edge,” says Frog King’s mentor Ming Fay, “Kwok became an outcast rebel.”(4) Here, the notion of endurance and existence is tested by the artist’s assiduous effort in being true to oneself and keeping aloof from the mainstream or conventions. In his performance, he often gives away objects, money, photocopies or even original copies of his own artwork to the audience. “The action itself makes it art,” explained Frog King, “I have nothing to lose, but people don’t understand”(5) . After all, Frog King is taking his whole life as a project – his playful, care-free and mischievous manner indeed is a strategy for seeking attention, opening up conversations and sharing with people including friends and strangers. He values spirituality higher than materials and such “de-commercialization” makes it hard for him survive in the art market system, let alone enjoy a well-off life in the materialistic sense.

Dancing in the Grand Arena

The title of the exhibition “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia” in Hong Kong pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale has well captured Frog King’s free and innovative spirit by making up words that look fun and amusing. “Frogtopia” means a place of frogs, as “topia” comes from the Greek word “topos” meaning a place or topic; “Hongkornucopia” implies an imagery of a vibrant city with multiplicities, as “cornucopia” means a magical goat’s horn with an inexhaustible store of fruit and grains coming out of it (6). The Chinese title (蛙托邦‧鴻港浩搞筆鴉) which sounds tongue twisting but gives an even more vivid feeling of Frog King’s playful characters: it juxtaposes an alternative transliteration of “Hong Kong” in Chinese, Frog King’s original name “Ho” and a word describing his action of graffiti painting.

At this point, one can imagine that dealing with such a bizarre artist as Frog King, especially for the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale, would be challenging for the curators as well as the organizers. The 53rd Venice Biennale attracted over 370 thousand visitors in 2009 (with a daily average of over 2000) (7) and the city itself has also benefited from cultural tourism generated by the Biennale, festivals and various related events. The Venice Biennale is like an expo, an art fair or even a grand arena, in which galleries, curators and artists are competing to stand out on the stage of international art; national pavilions are promoting their own countries or regions by showing their cultural landscapes and characters in the sense of global marketing. Opening ceremonies and parties during the preview days were attended by senior government officials and celebrities, and an invitation to the opening, dinner or after party of some prestigious pavilion is a symbol of privilege and status. Or, as pointed out by Carol Yinghua Lu, the young Chinese curator who sits on the Jury Panel of this year’s Venice Biennale Official Awards, the Venice Biennale nowadays is getting more and more commercialized and closely influenced by the global art market (8). Venice Biennale, after all, has been an art business where different stakeholders are maximizing their return on the work they invested, and idealism is far too distant to reach.

There is no doubt that Frog King, despite the extreme responses to his work, is eligible to represent Hong Kong in the Venice Biennale as one of the most important living artists in Hong Kong. Indeed, his representation of Hong Kong is a kind of recognition and affirmation of his professional achievements after years of diligence and struggle. Now the question is: how to fit a mischievous and rebellious artist into a grand mainstream system such as the Venice Biennale?

As envisioned by the Chairperson of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (also the commissioner of the Hong Kong pavilion), “the participation in the Venice Biennale will help strengthen ties and create new links between the Hong Kong arts community and its global counterparts and at the same time, show the best examples of Hong Kong's artists, promote local arts, and reinforce and raise the city's profile in the international arts world”(9). Hong Kong in its post-colonial era is desperate to search and build its identity since the Handover. The Venice Biennale has inevitably become a part of the global PR campaign. Hong Kong has been taking part in the Venice Biennale since 2001(10) and things have never gone smoothly. Every two years, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, which is responsible for the project, openly invites curators and arts organizations to submit proposals for exhibition. The first four participations in the International Art Exhibition were group shows or collective works while the 2009 and this year’s one have been solo exhibitions. Since 2006, the Hong Kong pavilion has moved to its current advantageous location at the opposite of the main entrance of Arsenale, one of the Biennale’s main exhibition venues.

Aside from controversies over the arrangements in previous years, the Hong Kong pavilion hit a roadblock and had to restart its application process last November after a complaint about the application procedure. The official announcement of vetting results was made in April, less than two months before the Biennale opened this year. No doubt, this has restricted the artist and curatorial team from detailed preparation and planning. Working with a talented and self-absorbed artist like Frog King, the best solution for the curators seems to be giving him free reign to do what he can in the limited time and to provide logistical support for the exhibition rather than trying to maintain control over everything.

A Feast of Froggy Vitality

Named “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia”, the exhibition is divided into 4 main segments: Frog Nest, Yum-Dimension Installation, 9 Million+ and the Frog-fun-lun Piazza in the courtyard, with installations where visitors can hang around for surprise performances, interventions or happenings by Frog King.

The exhibition itself is a big feast for visitors. Indeed, Frog King would never leave a place dull and static. The courtyard, or the Frog-fun-lun Piazza, is a jungle that welcomes the visitors with colorful clothes suspended above, as well as column-shaped paper boxes wrapped by the artist’s icons, plastic bottles and household objects hanging around. The walls are covered by gigantic paintings printed on banners, or some photos, drawings and collages cut in frog head shapes. Pieces of paper scattered around on the floor are evidence of his Frog-fun-lun; the bottles half-filled with buttons are indeed percussion instruments for everybody to have fun with and join in the Frog-fun-lun at any time.

When entering the indoor exhibition space, one might be lucky enough to see Frog King dressed up and striking a pose for photos with the audience in the first few weeks. To join the photo shots, you have to put on the froggy glasses, or even more, wigs, special hat, necklaces made from table-tennis balls or any other costumes provided, play the drums made from big tin containers and make funny gestures with Frog King. This is the world-wide Froggy Sunglasses Project that Frog King has been doing since 1989. On the wall inside the exhibition hall or in the kiosk there, you can find funny photos of people around the world – some are even celebrities – with froggy sunglasses. Such “one-second performances” or “one-second body installations” as conducted by Frog Kong during the photo shoots reveal a kind of “egalitarian” aesthetics of the artist in his project statement: “All beings on [the] earth are [of] equality.” By inviting people to put on the symbolic froggy sunglasses as he does, Frog King performs a magic to change others’ identity in a minute. As observed by Tsang, “this simple manipulation of identity transforms a mundane encounter into an epiphany that leads the audience members to step outside themselves”(11). Frog King’s costumes, on the other hand, also let him step out of his daily-life identity and plunge into mundane encounters with friends and strangers around the world. Whether it is “Art is frog; frog is art” or “Art is life; life is art”, the audience enters the froggy cosmos that embraces all kinds of vitality in an equal rather than divided manner. So, one would not be surprised to see people from all walks of life – even those who are punctilious and staid in manners – happy to stop by and have fun with Frog King. This happens the same way at the Hong Kong pavilion where people very much enjoyed the Froggy Sunglasses project. Their photos are added to the installation on site and absorbed into the froggy macrocosm.

Going further into the exhibition venue, there is the “Yum-Dimension Installation”. “Yum-Dimension” is another concept invented by Frog King. It represents the kind of openness and flexibility that one can achieve in art-making. No matter what or how the shape, quantity, medium, idea or dimensions are, Frog King attempts to work in a liberal and spontaneous manner. This is not about causal and indulgent improvisation but the mastery of skills and control over creative practices that leave no traces of overworking. It’s just like a Chinese saying: “one minute onstage requires 10 years of hard work offstage”. Practice makes perfect; and mastery cannot be attained in one day. “Yum-Dimension” implies a kind of mental or spiritual freedom that transcends skills or knowledge and sublimates the physical world, enduring an extensive range of cultivation. Such high-level spirituality has been often sought by artists or literati in traditional Chinese culture.

In the exhibition, there are a few gigantic door frames made of paper boxes and calligraphy in Frog King’s style as well assorted collages, ink paintings and calligraphy, photos of his previous projects and installations mixed together. The images are framed in froggy windows – boxes with two froggy eyes on the top, one looking inward and one outward – a metaphor for the artist’s world view in a dialectic and paradoxical manner. The maximalist style of installation with its profusion of images has assembled a hybrid and saturated atmosphere. The most interesting work, one which looks very different from the rest, is a set of 300 ceramic figurines of policemen from different generations in Hong Kong’s colonial era. Compared to other chaotic installations, the figurines, all painted in white, are standing rather quietly one by one in a squad at a dim corner by the wall and easily missed by the crowds. According to Frog King, the “Kwok’s Terracotta Army” was selected for the Hong Kong Art Biennial 2003, a bi-annual open competition-cum-exhibition that the Hong Kong Museum of Art used to organize, because most people (including the jury) could not recognize it as his work. Frog King has long been pushed out by the establishment owing to his avant-garde-ness and mischievousness. One can imagine that inclusion of the “Kwok’s Terracotta Army,” which is not consistent with his other works, in an official exhibition at the Venice Biennale could be a protest gesture aimed at the artist’s opponents. Alternatively, it can be read as the liberal and all-embracing nature of Frog King’s “Yum-Dimension” macrocosm where he would be able to break down, absorb, transform and revitalize all forms.

The other room connecting to the courtyard, titled “9 Million+,” contains edited video documentation of Frog King’s performances and other works shown on LCD screens. Video as a mediated form indeed often raises the dilemma of documenting or eliminating the liveness of performances. How to present an artist who is blurring art and life in video in a limited length of time? At first glance, the free-style action painting is bold and attention-grabbing. Changing the idea of pasting a big pre-made froggy painting on the wall, Frog King splashes ink on the wall and immediately turns the room into a vigorous and dynamic space in only a few minutes. Traces of his action on the wall make a remarkable contrast to the mediated documentation of his performances, and further cast his work in a paradoxical light. The contents of the videos then become unimportant; it is the experience that lets the audience contemplate the blurring of art and life, frog and life, and the live and mediated actions in an imaginative and open-ended setting.

Spirituality of an Abundant Self

So what is the magic of curating an exhibition for such a highly enthusiastic and strong-willed artist as Frog King with a coherent and sophisticated system? Other than seeking sponsorship and logistical arrangements, a high level of curatorship is needed to interpret and contextualize his work within an appropriate framework. The difficulty lies in finding a balance between opening up the possibilities of presenting the artist’s work in an accessible way and preserving the organic wholeness of his organism. Tsang Tak-ping, one of the curators and someone who studied with Frog King for long since college, conceived an inspirational idea: “the Frog Nest”, which is a home for Frog King to settle down and adapt his work on site. “In both his living space and his art installations, Frog King always aligns himself with a compact space that he has created using the objects he has assembled,” Tsang states, “and he derives security and a sense of controlled chaos when he works and performs in it, encircled by his objects”(12).

Bear in mind that exhibiting at the Venice Biennale is immensely competitive. Everyday an average of over 2,000 art tourists, who mostly have limited time, are stretched among the work of 83 artists in the main exhibition, a record-breaking 89 national pavilions and 37 collateral events scattered around the city this year. How to attract the audience and at the same time preserve the authentic spirit of the artist and his work would be a big challenge. To this extent, the idea of “Frog Nest” seems to be a good solution to present Frog King’s art and life by exhibiting his “living” in situ and let the audience interact with him and exchange energies instantaneously. The “Frog Nest” developed by Frog King during his month-long stay in the pavilion is both a physical and mental space for him to absorb his surroundings, to breed ideas and to revitalize the venue. It also provides an immediate experience for the audience who enter the pavilion in a lively and creative atmosphere – they can browse the pictures of other people who took part in the Froggy Sunglasses Project there, pick up or step on pieces of paper or even photocopies of work that was flying around in recently concluded happenings, talk to the artist as well as play with the objects, costumes and percussion gadgets, among many other activities.

This calls to mind the Icelandic pavilion at the last Venice Biennale (2009), which featured a tableau vivant of the artist and his model during the entire six-months of the Biennale. A kind of friendliness developed when one entered the space right away and saw the finished or unfinished paintings, heaps of emptied wine bottles, magazines and belongings scattered around the place. The artist and his model were hanging around, painting or talking to the visitors causally. Viewing the exhibition is more like visiting an artist’s studio or a peer’s home. It was especially refreshing after the intensive art-viewing experiences in Venice and offered a retreat from the bustling art business into an everyday life setting.

In contrast to conventional theatre in which actors perform characters in a more controlled and self-contained environment, performance art (or live art) requires exceptional skills in mastering the impermanence of here and now, or encounters with the audience in a particular time and space without any rehearsals or run-throughs of the actual situation. Through a series of refinement and alchemy, creativity is sublimated through continuous experimentation to become an immortal spirit that goes beyond material and physical skills. For Frog King, such spiritual pursuits can often be found in his work too. The liberal and playful attitude he shows in his work indeed comes as a result of his sophisticated practice through continuous exercise and experimentation over the years.

As elaborated by the Chinese aesthetic master Zong Baihua, “the highest level of humankind’s spiritual activity, the state of art and the state of philosophy, is born within the self deep in the freest and the most abundant heart. Such abundant self is full of pure energy, having everything aside, moving freely, detached and unrestrained; space is needed for his activities”(13). What he discusses here is the notion of ink “dancing” on paper in Chinese calligraphy, and the same theory can be applied in Frog King’s action, which is not limited to his performances but takes his practice of art-making as a series of actions. So the “Frog Nest” would be a home to Frog King’s abundant self, nourished by absorbing and sharing the pure energy with others and the universe.

In theory, the “Frog Nest” sounds like a perfect idea to present Frog King and his work in the Hong Kong pavilion, and in fact, most people were delighted and pleased to visit the exhibition during Frog King’s stay in the first few weeks. What about after the artist has gone; how to keep his spirit there afterwards? How to condense people’s experience of Frog King’s work after playing around and having fun? How to contextualize the artist and his body of work, which is loaded with traditional Chinese aesthetics within, say, the frameworks of the avant-garde movement, performance studies or the culture of Hong Kong, for the western audience? These questions are to be answered in the exhibition at the Hong Kong pavilion, and needed to be further explored in researching and examining the work of Frog King as one of the most important contemporary artists in Hong Kong.

A bizarre cross-media artist like Frog King, who has long been pushed out by the contemporary establishment, as Tsang points out too(14), is lacking the attention he deserves, not to mention a range of critical discourses to be developed upon his work from different perspectives and aspects or in different contexts. Limited preparation time is surely to blame, and delicate curatorship indeed requires concentrated energy, creative capacity and a broad vision. The Venice Biennale is a grand arena that would put Frog Kong in the spotlight, and on the other hand would also make his work a flash in the pan. Hong Kong, with its fast tempo, is often said to be a city of disappearance(15). The disappearance can be understood as a transcendence of (im)mortal life. However, I do hope, for an artist of great significance, the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale can be more than a city’s global marketing campaign or occasion to show-off but will open up possibilities of examining Hong Kong art and its identity in various contexts, especially before the artists and their artworks have vanished without a trace.

To raise a city’s profile requires more than squeezing into an international competition. One must nourish the culture of the city in a way that would affect others spiritually. For a city which has deserted its delicate cultural development for so long, have we been inspired by the all-embracing froggy macrocosm?

Footnotes:

(1) Happening: Splashing Cow Bone Action, 1975, Kwok-Art Life For 30 Years 1967-1997, 1999.

(2) Allan Kaprow: Happenings in the New York Scene (1961), Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, Jeff Kelley (ed), University of California Press, 1996, p.15-26

(3) Tsang Tak-ping, “Art is Life, Life is Art”: Frog King’s Art and Life as A Secular Pilgrimage of Illuminations, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.21

(4) Ming Fay: Tadpole to Frog King, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.30

(5) Dialogue Between Artist & Curators, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.37

(6) Benny Chia, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia: Reading Frog King Kwok, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.10

(7) Record year for Venice Biennale, The Art Newspaper, issue 208, December 2009.

(8) Carol Lu Yinghua: The Venice Biennale in Crisis, Sweekly, 20 June 2011.

(9) Frog King Kwok "LEAPS" from HK to Venice, Creating Frogtopia to Show his Artistic Uniqueness, press release, Hong Kong Arts Development Council, 03 June 2011.

(10) Hong Kong’s participation in the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition started from 2001 while the participation in the International Architecture Biennale started from 2005.

(11) Tsang Tak-ping, “Art is Life, Life is Art”: Frog King’s Art and Life as A Secular Pilgrimage of Illuminations, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.24.

(12) ibid., p.26.

(13) Zong Bai-hua: The Birth of the State of Mind in Chinese Art, Aesthetic Walk (Mei Xue De San Bu), Hung Fan Shu Dian, (宗白華:〈中國藝術意境之誕生〉,《美學的散步》洪範書店) 1981, p.15 (Translated by wen yau from the original quote).

(14) Tsang Tak-ping: Has Frog King been discussed enough? (蛙王被論盡了嗎?), Hong Kong Economic Journal, 14 April 2011.

(15) Such theory is best represented by Ackbar Abbas in his book: Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance, University Of Minnesota Press, 1997.

The 54th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition – Hong Kong Pavilion:

http://www.venicebiennale.hk/2011/

First published in Art in China, Issue 03, July-September 2011.

1. Frog King in full froggy costume.

2. Images of Frog King's work in froggy windows.

3. Traces of Frog King's action painting on the wall make a contemplative comparison to the video documentation of his performances, etc.

4. Frog King can never stop making art, and this work was produced in Venice during his stay in the Frog Nest (Photo courtesy of Frog King).

5. Frog King was doing calligraphy when visitors came to the pavilion (Photo courtesy of Frog King).

© All photos by wen yau unless specified.

(原文以英文發表,評論第54屆威尼斯雙年展香港館展覽《蛙托邦鴻港浩搞筆鴉》。)

(The website does not allow correct formatting of this document.)

Transcendence of (Im)mortal Life, Disappearance from the Bustling Arena, or Something Else?

A Review of “Frogtopia. Hongkornucopia” at the Venice Biennale

by wen yau

Talking about Frog King has never been an easy thing.

This year, at the 54th Venice Biennale, the Hong Kong pavilion presents veteran artist Kwok Mang-ho (aka Frog King) in an exhibition titled “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia.”

People often have extreme responses to Frog King and his work – some very much enjoy his interventions, happenings and performances, where paper flies everywhere and everybody is making music with plastic bottles, cooking pans and the like; some admire his vibrant creative energies that have kept his artistic career alive for over 40 years; some find his spontaneous, carefree and self-absorbed style and action bedeviling, and some complain that he has just been repeating himself in his work for years and not keeping up with current trends... However, one cannot deny the significance of Frog King as an innovative and pioneering artist in Hong Kong or even China.

Froggism: “Art is Life, Life is Art”

Frog King was the first artist to engage in performance art in Hong Kong and mainland China. In 1975, he dumped a bag of burnt cow bone next to his award-winning sculpture “Fire Sculpture” in the Contemporary Hong Kong Art exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, which organized the annual competition of the same title, and discussed artistic concepts with the audience. As the first documented happening or performance art piece in Hong Kong (1), Frog King’s action challenged institutional power and shifted the power of interpretation to the audience by inviting them to join in active participation. Audience participation pays a significant role in Frog King’s happenings or “Frog-fun-lun” (蛙玩臨) – a term that he adapted from the term “Hark Bun Lum” (客賓臨) he invented for his happenings in the 1970s, literally meaning “arrival of guests”. His fun and joyful performances are often highly attractive and enticing, pulling the audience in to participate.

On the other hand, Frog King studied with Lui Shou-Kwan, the master artist and advocate of the New Ink Painting Movement in Hong Kong during the 60s and onwards. Inspired by Lui, Frog King’s free-style ink painting and calligraphy brought the form and spirit of traditional Chinese art forward into today’s highly westernized cultural context. Distinguished by the abundance of images borrowed from popular culture, his work of collage using ink calligraphy, photos and images from newspapers or magazines illustrates the cosmos of love and harmony that can be found in traditional Chinese ink painting as well – this chaos of images, calligraphy and painting creates a surrealistic atmosphere through multiple perspectives and converges into a universe of wholeness. His recent series of Chinese calligraphy, which blends English into Chinese characters, also demonstrates Frog King’s continuing efforts to experiment with the medium and promote the spirit of Chinese ink painting in the contemporary context. Traces of the Zen and Tao philosophy that are deeply ingrained in traditional Chinese art can also be found throughout Frog King’s oeuvre. Out of the tangible and figurative images, he attempts to extract a kind of spiritual, poetic harmony.

The frog is a recurring motif in Frog King’s oeuvre. His signature or icon in the shape of a frog head with triangular crown or mountain-like eyes and a half-moon-like broad grin is probably the best example. The well-known froggy glasses that he keeps on making are for the project in which he invites people he meets randomly to put on and pose for snapshots. As he puts it, the frog is a kind of flexible and adaptive creature with strong vitality. At the age of 64, Frog King is still active in the local and international art scene. From Hong Kong to New York where he lived for 15 years (1980-1995) during the heyday of avant-garde art, and more recently Korea, Beijing and Shanghai where he has set up studios with his wife Cho Hyun-jae, Frog King leaps around swiftly, not confined by any forms, mediums or cultural differences. Plastic bags, rotten eggs, toilet paper, cloth, bras, paper of all sizes, roast suckling pigs, table-tennis balls or any other gadgets he picks up in everyday life are being used in his performances and installations in any places and at any time. Wherever he dons his layered “froggy” costume, his energy is so contagious that it draws in the audience.

When looking at Frog King’s motto: “Art is life, life is art” (or sometimes “Art is frog, frog is art”), one may think of other renowned artists such as Allan Kaprow, Tehching Hsieh and Marina Abramović. Somehow Frog King follows the cannon of Kaprow’s notion of happenings, which connotes a form of improvisation, fluidity, open-ended-ness, serendipity and impermanence as opposed to conventional theatre (2). Just like Hsieh’s One Year Performances in which the artist confined himself to certain extreme physical living and even existential conditions within a specific period of time, or Abramović’s very long durational pieces that push the boundary of one’s endurance, Frog King’s work is about the artist’s presence, sharing with others at every moment of here and now. Indeed, Frog King is making his creative practice a ritual of everyday life rather than separate component of it, a ritual of spiritual pursuit that purifies himself, his work and the world beyond the material.

Most people would be stunned by the vast amount of materials he keeps in his studio or the “Frog King Kwok Museum” which is a total project in and of itself. His museum houses documentation such as remnants, slides and photos of performances, exhibitions as well as everyday household objects he has collected and assembled for experimentation and exhibition, an abundance of the ink paintings and calligraphy he produced every day and many more things, all stored in a highly compact manner. This is a statement in itself, one that reveals his spatial aesthetics through populating and occupying physical space with his creative spirits. Tsang Tak Ping, one of the curators of this year’s Hong Kong Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, observes, “It forms a paradoxical landscape in which he uses objects and materials he has found to mock as well as transcend the materialistic world”(3). By packing physical spaces with the maximum amount of materials, he is like a martial arts master pushing himself in extreme conditions so as to attain spiritual transformation and advancement ascetically.

“Kwok was an innovator of an avant-garde art movement that no one dared to follow at a time when Hong Kong’s boundaries where defined by ancient tradition with a new edge,” says Frog King’s mentor Ming Fay, “Kwok became an outcast rebel.”(4) Here, the notion of endurance and existence is tested by the artist’s assiduous effort in being true to oneself and keeping aloof from the mainstream or conventions. In his performance, he often gives away objects, money, photocopies or even original copies of his own artwork to the audience. “The action itself makes it art,” explained Frog King, “I have nothing to lose, but people don’t understand”(5) . After all, Frog King is taking his whole life as a project – his playful, care-free and mischievous manner indeed is a strategy for seeking attention, opening up conversations and sharing with people including friends and strangers. He values spirituality higher than materials and such “de-commercialization” makes it hard for him survive in the art market system, let alone enjoy a well-off life in the materialistic sense.

Dancing in the Grand Arena

The title of the exhibition “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia” in Hong Kong pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale has well captured Frog King’s free and innovative spirit by making up words that look fun and amusing. “Frogtopia” means a place of frogs, as “topia” comes from the Greek word “topos” meaning a place or topic; “Hongkornucopia” implies an imagery of a vibrant city with multiplicities, as “cornucopia” means a magical goat’s horn with an inexhaustible store of fruit and grains coming out of it (6). The Chinese title (蛙托邦‧鴻港浩搞筆鴉) which sounds tongue twisting but gives an even more vivid feeling of Frog King’s playful characters: it juxtaposes an alternative transliteration of “Hong Kong” in Chinese, Frog King’s original name “Ho” and a word describing his action of graffiti painting.

At this point, one can imagine that dealing with such a bizarre artist as Frog King, especially for the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale, would be challenging for the curators as well as the organizers. The 53rd Venice Biennale attracted over 370 thousand visitors in 2009 (with a daily average of over 2000) (7) and the city itself has also benefited from cultural tourism generated by the Biennale, festivals and various related events. The Venice Biennale is like an expo, an art fair or even a grand arena, in which galleries, curators and artists are competing to stand out on the stage of international art; national pavilions are promoting their own countries or regions by showing their cultural landscapes and characters in the sense of global marketing. Opening ceremonies and parties during the preview days were attended by senior government officials and celebrities, and an invitation to the opening, dinner or after party of some prestigious pavilion is a symbol of privilege and status. Or, as pointed out by Carol Yinghua Lu, the young Chinese curator who sits on the Jury Panel of this year’s Venice Biennale Official Awards, the Venice Biennale nowadays is getting more and more commercialized and closely influenced by the global art market (8). Venice Biennale, after all, has been an art business where different stakeholders are maximizing their return on the work they invested, and idealism is far too distant to reach.

There is no doubt that Frog King, despite the extreme responses to his work, is eligible to represent Hong Kong in the Venice Biennale as one of the most important living artists in Hong Kong. Indeed, his representation of Hong Kong is a kind of recognition and affirmation of his professional achievements after years of diligence and struggle. Now the question is: how to fit a mischievous and rebellious artist into a grand mainstream system such as the Venice Biennale?

As envisioned by the Chairperson of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (also the commissioner of the Hong Kong pavilion), “the participation in the Venice Biennale will help strengthen ties and create new links between the Hong Kong arts community and its global counterparts and at the same time, show the best examples of Hong Kong's artists, promote local arts, and reinforce and raise the city's profile in the international arts world”(9). Hong Kong in its post-colonial era is desperate to search and build its identity since the Handover. The Venice Biennale has inevitably become a part of the global PR campaign. Hong Kong has been taking part in the Venice Biennale since 2001(10) and things have never gone smoothly. Every two years, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, which is responsible for the project, openly invites curators and arts organizations to submit proposals for exhibition. The first four participations in the International Art Exhibition were group shows or collective works while the 2009 and this year’s one have been solo exhibitions. Since 2006, the Hong Kong pavilion has moved to its current advantageous location at the opposite of the main entrance of Arsenale, one of the Biennale’s main exhibition venues.

Aside from controversies over the arrangements in previous years, the Hong Kong pavilion hit a roadblock and had to restart its application process last November after a complaint about the application procedure. The official announcement of vetting results was made in April, less than two months before the Biennale opened this year. No doubt, this has restricted the artist and curatorial team from detailed preparation and planning. Working with a talented and self-absorbed artist like Frog King, the best solution for the curators seems to be giving him free reign to do what he can in the limited time and to provide logistical support for the exhibition rather than trying to maintain control over everything.

A Feast of Froggy Vitality

Named “Frogtopia • Hongkornucopia”, the exhibition is divided into 4 main segments: Frog Nest, Yum-Dimension Installation, 9 Million+ and the Frog-fun-lun Piazza in the courtyard, with installations where visitors can hang around for surprise performances, interventions or happenings by Frog King.

The exhibition itself is a big feast for visitors. Indeed, Frog King would never leave a place dull and static. The courtyard, or the Frog-fun-lun Piazza, is a jungle that welcomes the visitors with colorful clothes suspended above, as well as column-shaped paper boxes wrapped by the artist’s icons, plastic bottles and household objects hanging around. The walls are covered by gigantic paintings printed on banners, or some photos, drawings and collages cut in frog head shapes. Pieces of paper scattered around on the floor are evidence of his Frog-fun-lun; the bottles half-filled with buttons are indeed percussion instruments for everybody to have fun with and join in the Frog-fun-lun at any time.

When entering the indoor exhibition space, one might be lucky enough to see Frog King dressed up and striking a pose for photos with the audience in the first few weeks. To join the photo shots, you have to put on the froggy glasses, or even more, wigs, special hat, necklaces made from table-tennis balls or any other costumes provided, play the drums made from big tin containers and make funny gestures with Frog King. This is the world-wide Froggy Sunglasses Project that Frog King has been doing since 1989. On the wall inside the exhibition hall or in the kiosk there, you can find funny photos of people around the world – some are even celebrities – with froggy sunglasses. Such “one-second performances” or “one-second body installations” as conducted by Frog Kong during the photo shoots reveal a kind of “egalitarian” aesthetics of the artist in his project statement: “All beings on [the] earth are [of] equality.” By inviting people to put on the symbolic froggy sunglasses as he does, Frog King performs a magic to change others’ identity in a minute. As observed by Tsang, “this simple manipulation of identity transforms a mundane encounter into an epiphany that leads the audience members to step outside themselves”(11). Frog King’s costumes, on the other hand, also let him step out of his daily-life identity and plunge into mundane encounters with friends and strangers around the world. Whether it is “Art is frog; frog is art” or “Art is life; life is art”, the audience enters the froggy cosmos that embraces all kinds of vitality in an equal rather than divided manner. So, one would not be surprised to see people from all walks of life – even those who are punctilious and staid in manners – happy to stop by and have fun with Frog King. This happens the same way at the Hong Kong pavilion where people very much enjoyed the Froggy Sunglasses project. Their photos are added to the installation on site and absorbed into the froggy macrocosm.

Going further into the exhibition venue, there is the “Yum-Dimension Installation”. “Yum-Dimension” is another concept invented by Frog King. It represents the kind of openness and flexibility that one can achieve in art-making. No matter what or how the shape, quantity, medium, idea or dimensions are, Frog King attempts to work in a liberal and spontaneous manner. This is not about causal and indulgent improvisation but the mastery of skills and control over creative practices that leave no traces of overworking. It’s just like a Chinese saying: “one minute onstage requires 10 years of hard work offstage”. Practice makes perfect; and mastery cannot be attained in one day. “Yum-Dimension” implies a kind of mental or spiritual freedom that transcends skills or knowledge and sublimates the physical world, enduring an extensive range of cultivation. Such high-level spirituality has been often sought by artists or literati in traditional Chinese culture.

In the exhibition, there are a few gigantic door frames made of paper boxes and calligraphy in Frog King’s style as well assorted collages, ink paintings and calligraphy, photos of his previous projects and installations mixed together. The images are framed in froggy windows – boxes with two froggy eyes on the top, one looking inward and one outward – a metaphor for the artist’s world view in a dialectic and paradoxical manner. The maximalist style of installation with its profusion of images has assembled a hybrid and saturated atmosphere. The most interesting work, one which looks very different from the rest, is a set of 300 ceramic figurines of policemen from different generations in Hong Kong’s colonial era. Compared to other chaotic installations, the figurines, all painted in white, are standing rather quietly one by one in a squad at a dim corner by the wall and easily missed by the crowds. According to Frog King, the “Kwok’s Terracotta Army” was selected for the Hong Kong Art Biennial 2003, a bi-annual open competition-cum-exhibition that the Hong Kong Museum of Art used to organize, because most people (including the jury) could not recognize it as his work. Frog King has long been pushed out by the establishment owing to his avant-garde-ness and mischievousness. One can imagine that inclusion of the “Kwok’s Terracotta Army,” which is not consistent with his other works, in an official exhibition at the Venice Biennale could be a protest gesture aimed at the artist’s opponents. Alternatively, it can be read as the liberal and all-embracing nature of Frog King’s “Yum-Dimension” macrocosm where he would be able to break down, absorb, transform and revitalize all forms.

The other room connecting to the courtyard, titled “9 Million+,” contains edited video documentation of Frog King’s performances and other works shown on LCD screens. Video as a mediated form indeed often raises the dilemma of documenting or eliminating the liveness of performances. How to present an artist who is blurring art and life in video in a limited length of time? At first glance, the free-style action painting is bold and attention-grabbing. Changing the idea of pasting a big pre-made froggy painting on the wall, Frog King splashes ink on the wall and immediately turns the room into a vigorous and dynamic space in only a few minutes. Traces of his action on the wall make a remarkable contrast to the mediated documentation of his performances, and further cast his work in a paradoxical light. The contents of the videos then become unimportant; it is the experience that lets the audience contemplate the blurring of art and life, frog and life, and the live and mediated actions in an imaginative and open-ended setting.

Spirituality of an Abundant Self

So what is the magic of curating an exhibition for such a highly enthusiastic and strong-willed artist as Frog King with a coherent and sophisticated system? Other than seeking sponsorship and logistical arrangements, a high level of curatorship is needed to interpret and contextualize his work within an appropriate framework. The difficulty lies in finding a balance between opening up the possibilities of presenting the artist’s work in an accessible way and preserving the organic wholeness of his organism. Tsang Tak-ping, one of the curators and someone who studied with Frog King for long since college, conceived an inspirational idea: “the Frog Nest”, which is a home for Frog King to settle down and adapt his work on site. “In both his living space and his art installations, Frog King always aligns himself with a compact space that he has created using the objects he has assembled,” Tsang states, “and he derives security and a sense of controlled chaos when he works and performs in it, encircled by his objects”(12).

Bear in mind that exhibiting at the Venice Biennale is immensely competitive. Everyday an average of over 2,000 art tourists, who mostly have limited time, are stretched among the work of 83 artists in the main exhibition, a record-breaking 89 national pavilions and 37 collateral events scattered around the city this year. How to attract the audience and at the same time preserve the authentic spirit of the artist and his work would be a big challenge. To this extent, the idea of “Frog Nest” seems to be a good solution to present Frog King’s art and life by exhibiting his “living” in situ and let the audience interact with him and exchange energies instantaneously. The “Frog Nest” developed by Frog King during his month-long stay in the pavilion is both a physical and mental space for him to absorb his surroundings, to breed ideas and to revitalize the venue. It also provides an immediate experience for the audience who enter the pavilion in a lively and creative atmosphere – they can browse the pictures of other people who took part in the Froggy Sunglasses Project there, pick up or step on pieces of paper or even photocopies of work that was flying around in recently concluded happenings, talk to the artist as well as play with the objects, costumes and percussion gadgets, among many other activities.

This calls to mind the Icelandic pavilion at the last Venice Biennale (2009), which featured a tableau vivant of the artist and his model during the entire six-months of the Biennale. A kind of friendliness developed when one entered the space right away and saw the finished or unfinished paintings, heaps of emptied wine bottles, magazines and belongings scattered around the place. The artist and his model were hanging around, painting or talking to the visitors causally. Viewing the exhibition is more like visiting an artist’s studio or a peer’s home. It was especially refreshing after the intensive art-viewing experiences in Venice and offered a retreat from the bustling art business into an everyday life setting.

In contrast to conventional theatre in which actors perform characters in a more controlled and self-contained environment, performance art (or live art) requires exceptional skills in mastering the impermanence of here and now, or encounters with the audience in a particular time and space without any rehearsals or run-throughs of the actual situation. Through a series of refinement and alchemy, creativity is sublimated through continuous experimentation to become an immortal spirit that goes beyond material and physical skills. For Frog King, such spiritual pursuits can often be found in his work too. The liberal and playful attitude he shows in his work indeed comes as a result of his sophisticated practice through continuous exercise and experimentation over the years.

As elaborated by the Chinese aesthetic master Zong Baihua, “the highest level of humankind’s spiritual activity, the state of art and the state of philosophy, is born within the self deep in the freest and the most abundant heart. Such abundant self is full of pure energy, having everything aside, moving freely, detached and unrestrained; space is needed for his activities”(13). What he discusses here is the notion of ink “dancing” on paper in Chinese calligraphy, and the same theory can be applied in Frog King’s action, which is not limited to his performances but takes his practice of art-making as a series of actions. So the “Frog Nest” would be a home to Frog King’s abundant self, nourished by absorbing and sharing the pure energy with others and the universe.

In theory, the “Frog Nest” sounds like a perfect idea to present Frog King and his work in the Hong Kong pavilion, and in fact, most people were delighted and pleased to visit the exhibition during Frog King’s stay in the first few weeks. What about after the artist has gone; how to keep his spirit there afterwards? How to condense people’s experience of Frog King’s work after playing around and having fun? How to contextualize the artist and his body of work, which is loaded with traditional Chinese aesthetics within, say, the frameworks of the avant-garde movement, performance studies or the culture of Hong Kong, for the western audience? These questions are to be answered in the exhibition at the Hong Kong pavilion, and needed to be further explored in researching and examining the work of Frog King as one of the most important contemporary artists in Hong Kong.

A bizarre cross-media artist like Frog King, who has long been pushed out by the contemporary establishment, as Tsang points out too(14), is lacking the attention he deserves, not to mention a range of critical discourses to be developed upon his work from different perspectives and aspects or in different contexts. Limited preparation time is surely to blame, and delicate curatorship indeed requires concentrated energy, creative capacity and a broad vision. The Venice Biennale is a grand arena that would put Frog Kong in the spotlight, and on the other hand would also make his work a flash in the pan. Hong Kong, with its fast tempo, is often said to be a city of disappearance(15). The disappearance can be understood as a transcendence of (im)mortal life. However, I do hope, for an artist of great significance, the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale can be more than a city’s global marketing campaign or occasion to show-off but will open up possibilities of examining Hong Kong art and its identity in various contexts, especially before the artists and their artworks have vanished without a trace.

To raise a city’s profile requires more than squeezing into an international competition. One must nourish the culture of the city in a way that would affect others spiritually. For a city which has deserted its delicate cultural development for so long, have we been inspired by the all-embracing froggy macrocosm?

Footnotes:

(1) Happening: Splashing Cow Bone Action, 1975, Kwok-Art Life For 30 Years 1967-1997, 1999.

(2) Allan Kaprow: Happenings in the New York Scene (1961), Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, Jeff Kelley (ed), University of California Press, 1996, p.15-26

(3) Tsang Tak-ping, “Art is Life, Life is Art”: Frog King’s Art and Life as A Secular Pilgrimage of Illuminations, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.21

(4) Ming Fay: Tadpole to Frog King, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.30

(5) Dialogue Between Artist & Curators, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.37

(6) Benny Chia, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia: Reading Frog King Kwok, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.10

(7) Record year for Venice Biennale, The Art Newspaper, issue 208, December 2009.

(8) Carol Lu Yinghua: The Venice Biennale in Crisis, Sweekly, 20 June 2011.

(9) Frog King Kwok "LEAPS" from HK to Venice, Creating Frogtopia to Show his Artistic Uniqueness, press release, Hong Kong Arts Development Council, 03 June 2011.

(10) Hong Kong’s participation in the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition started from 2001 while the participation in the International Architecture Biennale started from 2005.

(11) Tsang Tak-ping, “Art is Life, Life is Art”: Frog King’s Art and Life as A Secular Pilgrimage of Illuminations, Frogtopia ‧ Hongkornucopia exhibition catalogue, p.24.

(12) ibid., p.26.

(13) Zong Bai-hua: The Birth of the State of Mind in Chinese Art, Aesthetic Walk (Mei Xue De San Bu), Hung Fan Shu Dian, (宗白華:〈中國藝術意境之誕生〉,《美學的散步》洪範書店) 1981, p.15 (Translated by wen yau from the original quote).

(14) Tsang Tak-ping: Has Frog King been discussed enough? (蛙王被論盡了嗎?), Hong Kong Economic Journal, 14 April 2011.

(15) Such theory is best represented by Ackbar Abbas in his book: Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance, University Of Minnesota Press, 1997.

The 54th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition – Hong Kong Pavilion:

http://www.venicebiennale.hk/2011/

First published in Art in China, Issue 03, July-September 2011.