Reviews & Articles

一輩子的「錯」? ∣ Being 'Wrong' Forever?

John BATTEN

at 10:35pm on 19th October 2016

Captions:

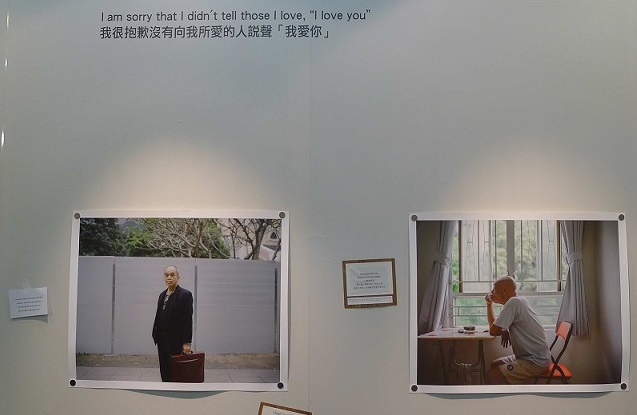

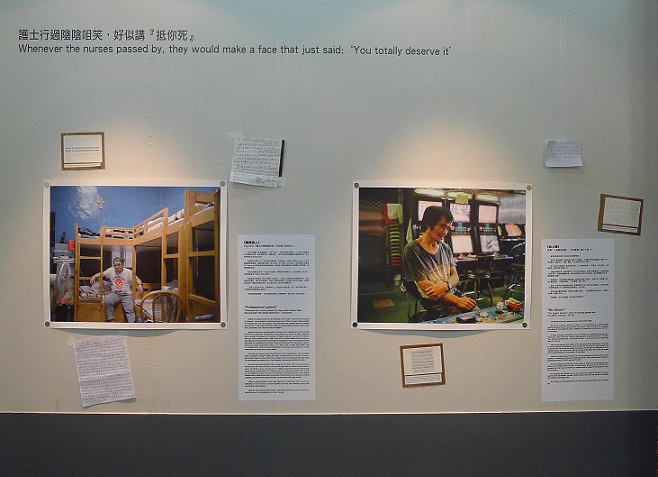

1. – 3. Installation views at SoCO Confessions exhibition, 2016

4. Confessions booth, Confessions exhibition, 2016

Photographs: John Batten

(Please scroll down for English version)

在1980年代時,我在紐西蘭從事社會/社區工作,服務一家在囚人士福利機構。具體來說,我領導一項「更新」計劃,協助那些以男性為主的釋囚重返外面的世界。我們提供工作機會和支援的環境。機構由一位作風嚴謹、進取的毛利女士主理廉租宿舍,並提供健康飲食。理想而言,機構可提供為期約一年的支援,幫助更新人士重新「腳踏實地」,讓他們在相對穩定的環境賺取由政府津貼的薪金,逐步邁向獨立。

我相信對於機構以及那些曾長時間在囚的更新人士來說,成功的一大考驗在於可以在社會上和財務上獨立:可以作出決定、有所選擇,而無須依賴機構、社會福利撥款和社會工作者等「專家」為他們介入。

任何曾干犯刑事罪行並在監獄服役的人士,在重返社會過獨立生活的過程中普遍遇上障礙:從鐵窗回到社會時每每難以撕去曾身陷囹圄的標籤。社交和家庭網絡對所有人都十分重要,但如果更新人士本身的網絡已失效又或面對各種問題,便會影響他們改過自身,因為家人與朋友或許無法提供幫助。老「朋友」可能就是入獄前一同濫藥的一群。而大部份情況,藥物、酒精和債務幾個因素,加上原有的個人、行為和社交問題,往往正是令人入獄的原因,而且很可能再犯和入獄。工作是無縫地重投社會的最佳方法:每天上班有著一定隱性埋名的作用,可以和其他同事打成一片,當然,穩定的收入讓更新人士可以有更多選擇的機會,也較易作出個人抉擇。但是,如果你曾是罪犯,有人會給你提供工作機會嗎?

香港社區組織協會舉辦的「《剖白》- 在囚及更生人士展覽」,和與展覽同期發佈的林振東影集《囚》來得正是合時。長久以來,市民都對香港政府的房屋、城市規劃、教育、文化保育、貧窮和生活負擔能力等方面的政策不滿,香港正面對未來如何繼續走下去的問題。最近,我們看到政府為低收入在職人士推出交通津貼,也為長者提供交通優惠。近年也有更多社區支援,回應城中少數族裔和與主流不同群體(例如同性戀、跨性別、變性人士社群)的需要。香港社區組織協會素來為不同社群爭取權利,包括貧窮人士、長者、病患者、新移民(特別是剛從內地來港的女性)、難民、露宿者,還有居住於惡劣環境(特別是非法劏房和籠屋)的兒童和家庭。然而,釋囚的故事卻難於啟齒:廣大市民對於監獄和法律制度認識不多,而且對於「曾經犯錯」的人沒有多少同情心。

1942年的《貝佛里奇報告書》(Beveridge Report) 探討了英國的貧窮和不平等問題,促使1945年剛勝出選舉的英國工黨政府推動多項徹底的社會政策,包括國民保健服務、逐步改善的社會福利和開明的教育政策。香港從英國繼承了一部份社會政策意念,例如免費的全民健康服務和公共房屋,但是香港最近卻少有討論對社會政策的選擇。我在唸大學時深受倫敦政治經濟學院社會研究學者李察.蒂特馬斯(1907-1973)的著作影響,他解釋了《貝佛里奇報告書》的複雜之處,說明了推動社會更公平的選擇和理念。我們需要這類討論,特別是至今仍有人認為,先讓一小部份商家富起來(例如香港的地產商),社會上所有人都會得到財富「潤澤」。

香港社區組織協會的展覽採取了非常個人化的方向來討論更新人士,向參觀者提問,讓他們回想自己過往曾否做出「錯誤」或令自己「後悔」的事。剎那的錯是否應該主宰未來的人生? 社會如何寬恕?隨著社會提出各種問題和不斷改變,這個反省方向更顯得合情合理。我們如何協助那些有需要的人再次獨立,成為活躍於社會、貢獻社會的一份子?我們又如何規劃更具社會公義的未來?

瀏覽更多資料:

《剖白》- 在囚及更生人士展覽 @ SoCO269展覽館

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2016年10月15日。

Translated from English into Chinese by Aulina Chan.

Being 'Wrong' Forever?

John Batten

In the 1980s I worked in New Zealand as a social/community worker in a prisoners’ welfare organization. Specifically, I led a ‘rehabilitation’ programme that bridged the release from prison to life in the outside world for those, mainly men, who had been in prison. We offered work opportunities and a supportive environment. Our organization also ran a hostel with low-cost accommodation and, importantly, served healthy meals – run by a very strict, assertive Maori woman, with – usually - a heart of gold! Ideally, it offered support for about one year and assisted a person to ‘get back on their feet’; offering a period of relative stability and (government-subsidised) wages enabling personal independence.

I suppose the test of success for all of us, including those that have been inside prison for a long period of time, is to be socially and financially independent – to make decisions, have choices, and not rely on institutions, social welfare payments and ‘experts’, such as social workers, to intervene on their behalf.

For anyone with a criminal conviction and time spent in prison, the barriers to achieve independence are universal, no matter the country or culture. The stigma of having been in prison is difficult to shake off once a person has been released and back in society. The usual social and family networks, so necessary for all of us, can be problematic for the ex-offender trying to go “straight” if those networks are themselves dysfunction or under stress. ‘Help’ from family and friends may not exist. Your old ‘friends’ could be the same friends you do drugs with. And in most cases, it is drugs, alcohol and debt combined with underlying personal, behavioural and social issues that both led to a person going to prison and to possibly reoffend and return. The best way to seamlessly re-enter society is to have a job. There is anonymity in going to work every day, you blend in with everyone else; and, of course, a regular salary allows choices to be made and easier personal decision-making. But, will someone offer you are job if you are an ex-offender?

The Society of Community Organization’s (SoCO) Confession - A Prisoners’ and Ex-offenders Exhibition and their accompanying photobook Prisoners by photographer Lam Chun Tung are timely. Hong Kong is facing questions in how to go forward with public dissatisfaction with long-standing government policies about housing, urban planning, education, heritage conservation, poverty and affordability. Recently, we have seen the introduction of a travel-subsidy for low-wage workers and travel concessions for the elderly. And in recent years, there is much more community support for minorities and people who are different, such as the city’s LGBT community. SoCO has long advocated the rights of the poor, elderly, the sick, new immigrants to Hong Kong (especially woman newly arrived from the mainland), refugees, the homeless and children and families living in substandard accommodation – especially illegal subdivided flats and cage-homes. But, ex-offenders are a difficult story to tell: the wider community has little or no experience of prisons and the legal system and there is little sympathy for those that “have done wrong.”

The 1942 Beveridge Report that enquired into poverty and inequality in Britain led to radical social policies being implemented by the newly elected 1945 British Labour Government. Consequently, the National Health Service, progressive social welfare benefits and liberal education policies were implemented. Hong Kong has inherited some of these social policy ideas (such as a free universal health care service and public housing) from Britain. But, Hong Kong’s recent discussions on social policy choices have been limited. I was highly influenced at university by the writings of Richard Titmuss (1907-1973), a social researcher at the London School of Economics who explained the complexities of the Beveridge Report and choices and philosophies that lead to a fairer society. It is a necessary discussion and particularly when we continue to hear the old, discredited argument that wealth will “trickle-down” to all members of society if we allow monopolies (such as property developers in Hong Kong) to succeed.

The SoCO exhibition takes a very personal approach in discussing ex-offenders: it asks visitors if they have previously done something “wrong” which they “regret.” Should a moment’s mistake govern your future? And, how does society forgive? As society questions and changes, this approach is very sensible. How do we assist those in need and to be independent and be active and contributing members of society? And, how do we plan a future with greater social justice?

Link for further info:

'Confessions – A Prisoners' and Ex-Offenders Exhibition' @ SoCO269 Exhibition Centre

This article was originally published in Ming Pao Weekly, 15 October 2016.

1. – 3. Installation views at SoCO Confessions exhibition, 2016

4. Confessions booth, Confessions exhibition, 2016

Photographs: John Batten

(Please scroll down for English version)

在1980年代時,我在紐西蘭從事社會/社區工作,服務一家在囚人士福利機構。具體來說,我領導一項「更新」計劃,協助那些以男性為主的釋囚重返外面的世界。我們提供工作機會和支援的環境。機構由一位作風嚴謹、進取的毛利女士主理廉租宿舍,並提供健康飲食。理想而言,機構可提供為期約一年的支援,幫助更新人士重新「腳踏實地」,讓他們在相對穩定的環境賺取由政府津貼的薪金,逐步邁向獨立。

我相信對於機構以及那些曾長時間在囚的更新人士來說,成功的一大考驗在於可以在社會上和財務上獨立:可以作出決定、有所選擇,而無須依賴機構、社會福利撥款和社會工作者等「專家」為他們介入。

任何曾干犯刑事罪行並在監獄服役的人士,在重返社會過獨立生活的過程中普遍遇上障礙:從鐵窗回到社會時每每難以撕去曾身陷囹圄的標籤。社交和家庭網絡對所有人都十分重要,但如果更新人士本身的網絡已失效又或面對各種問題,便會影響他們改過自身,因為家人與朋友或許無法提供幫助。老「朋友」可能就是入獄前一同濫藥的一群。而大部份情況,藥物、酒精和債務幾個因素,加上原有的個人、行為和社交問題,往往正是令人入獄的原因,而且很可能再犯和入獄。工作是無縫地重投社會的最佳方法:每天上班有著一定隱性埋名的作用,可以和其他同事打成一片,當然,穩定的收入讓更新人士可以有更多選擇的機會,也較易作出個人抉擇。但是,如果你曾是罪犯,有人會給你提供工作機會嗎?

香港社區組織協會舉辦的「《剖白》- 在囚及更生人士展覽」,和與展覽同期發佈的林振東影集《囚》來得正是合時。長久以來,市民都對香港政府的房屋、城市規劃、教育、文化保育、貧窮和生活負擔能力等方面的政策不滿,香港正面對未來如何繼續走下去的問題。最近,我們看到政府為低收入在職人士推出交通津貼,也為長者提供交通優惠。近年也有更多社區支援,回應城中少數族裔和與主流不同群體(例如同性戀、跨性別、變性人士社群)的需要。香港社區組織協會素來為不同社群爭取權利,包括貧窮人士、長者、病患者、新移民(特別是剛從內地來港的女性)、難民、露宿者,還有居住於惡劣環境(特別是非法劏房和籠屋)的兒童和家庭。然而,釋囚的故事卻難於啟齒:廣大市民對於監獄和法律制度認識不多,而且對於「曾經犯錯」的人沒有多少同情心。

1942年的《貝佛里奇報告書》(Beveridge Report) 探討了英國的貧窮和不平等問題,促使1945年剛勝出選舉的英國工黨政府推動多項徹底的社會政策,包括國民保健服務、逐步改善的社會福利和開明的教育政策。香港從英國繼承了一部份社會政策意念,例如免費的全民健康服務和公共房屋,但是香港最近卻少有討論對社會政策的選擇。我在唸大學時深受倫敦政治經濟學院社會研究學者李察.蒂特馬斯(1907-1973)的著作影響,他解釋了《貝佛里奇報告書》的複雜之處,說明了推動社會更公平的選擇和理念。我們需要這類討論,特別是至今仍有人認為,先讓一小部份商家富起來(例如香港的地產商),社會上所有人都會得到財富「潤澤」。

香港社區組織協會的展覽採取了非常個人化的方向來討論更新人士,向參觀者提問,讓他們回想自己過往曾否做出「錯誤」或令自己「後悔」的事。剎那的錯是否應該主宰未來的人生? 社會如何寬恕?隨著社會提出各種問題和不斷改變,這個反省方向更顯得合情合理。我們如何協助那些有需要的人再次獨立,成為活躍於社會、貢獻社會的一份子?我們又如何規劃更具社會公義的未來?

瀏覽更多資料:

《剖白》- 在囚及更生人士展覽 @ SoCO269展覽館

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2016年10月15日。

Translated from English into Chinese by Aulina Chan.

Being 'Wrong' Forever?

John Batten

In the 1980s I worked in New Zealand as a social/community worker in a prisoners’ welfare organization. Specifically, I led a ‘rehabilitation’ programme that bridged the release from prison to life in the outside world for those, mainly men, who had been in prison. We offered work opportunities and a supportive environment. Our organization also ran a hostel with low-cost accommodation and, importantly, served healthy meals – run by a very strict, assertive Maori woman, with – usually - a heart of gold! Ideally, it offered support for about one year and assisted a person to ‘get back on their feet’; offering a period of relative stability and (government-subsidised) wages enabling personal independence.

I suppose the test of success for all of us, including those that have been inside prison for a long period of time, is to be socially and financially independent – to make decisions, have choices, and not rely on institutions, social welfare payments and ‘experts’, such as social workers, to intervene on their behalf.

For anyone with a criminal conviction and time spent in prison, the barriers to achieve independence are universal, no matter the country or culture. The stigma of having been in prison is difficult to shake off once a person has been released and back in society. The usual social and family networks, so necessary for all of us, can be problematic for the ex-offender trying to go “straight” if those networks are themselves dysfunction or under stress. ‘Help’ from family and friends may not exist. Your old ‘friends’ could be the same friends you do drugs with. And in most cases, it is drugs, alcohol and debt combined with underlying personal, behavioural and social issues that both led to a person going to prison and to possibly reoffend and return. The best way to seamlessly re-enter society is to have a job. There is anonymity in going to work every day, you blend in with everyone else; and, of course, a regular salary allows choices to be made and easier personal decision-making. But, will someone offer you are job if you are an ex-offender?

The Society of Community Organization’s (SoCO) Confession - A Prisoners’ and Ex-offenders Exhibition and their accompanying photobook Prisoners by photographer Lam Chun Tung are timely. Hong Kong is facing questions in how to go forward with public dissatisfaction with long-standing government policies about housing, urban planning, education, heritage conservation, poverty and affordability. Recently, we have seen the introduction of a travel-subsidy for low-wage workers and travel concessions for the elderly. And in recent years, there is much more community support for minorities and people who are different, such as the city’s LGBT community. SoCO has long advocated the rights of the poor, elderly, the sick, new immigrants to Hong Kong (especially woman newly arrived from the mainland), refugees, the homeless and children and families living in substandard accommodation – especially illegal subdivided flats and cage-homes. But, ex-offenders are a difficult story to tell: the wider community has little or no experience of prisons and the legal system and there is little sympathy for those that “have done wrong.”

The 1942 Beveridge Report that enquired into poverty and inequality in Britain led to radical social policies being implemented by the newly elected 1945 British Labour Government. Consequently, the National Health Service, progressive social welfare benefits and liberal education policies were implemented. Hong Kong has inherited some of these social policy ideas (such as a free universal health care service and public housing) from Britain. But, Hong Kong’s recent discussions on social policy choices have been limited. I was highly influenced at university by the writings of Richard Titmuss (1907-1973), a social researcher at the London School of Economics who explained the complexities of the Beveridge Report and choices and philosophies that lead to a fairer society. It is a necessary discussion and particularly when we continue to hear the old, discredited argument that wealth will “trickle-down” to all members of society if we allow monopolies (such as property developers in Hong Kong) to succeed.

The SoCO exhibition takes a very personal approach in discussing ex-offenders: it asks visitors if they have previously done something “wrong” which they “regret.” Should a moment’s mistake govern your future? And, how does society forgive? As society questions and changes, this approach is very sensible. How do we assist those in need and to be independent and be active and contributing members of society? And, how do we plan a future with greater social justice?

Link for further info:

'Confessions – A Prisoners' and Ex-Offenders Exhibition' @ SoCO269 Exhibition Centre

This article was originally published in Ming Pao Weekly, 15 October 2016.