Reviews & Articles

泰國的和解訊息 ∣ A Thai Reconciliation Message

John BATTEN

at 1:03pm on 21st November 2017

Caption:

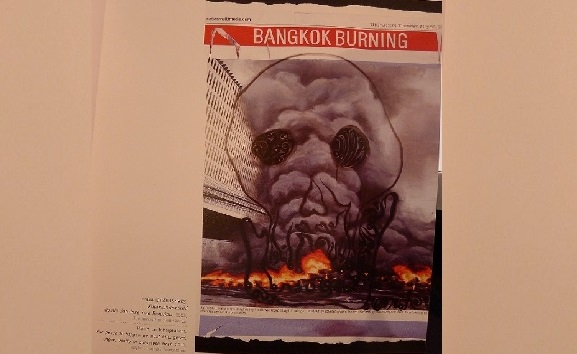

Kamin Lertchaiprasert, For peace to happen we must kill...greed, anger, vanity, in ourselves first, 140x220cm, acrylic on canvas, 2010 (image taken from exhibition catalogue)

(Please scroll down for English version)

政治陰謀是泰國的常態;在較明顯的泰國佛教與靈性節奏中,它的存在可說是世俗的暗湧。過去幾個月,全國悼念泰王普密蓬(拉瑪九世),在他離世至兩星期前舉行公眾葬禮和私人火葬期間,政治似乎擱在一旁,最少在公眾目光下如是。

2010年在泰國發生的政治動亂,以及2013-14年親政府紅衫軍(支持前總理德信與他妹妹,即時任總理英祿的人士)以及反政府抗議人士(稱為黃衫軍)之間暴力的街頭衝突,促成了2014年5月由陸軍司令巴育率領的軍事政變。巴育把大部份泰國憲法懸空,現時率領一個未經選舉產生的軍政府。這是站不住腳的,但卻是保持街上不再出現其他抗議的鎖定狀態。儘管軍政府已承諾於2018年11月舉行大選,但在軍方保留絕對權力的新憲法下,讓平民管治回歸,毫無疑問,將需要閉門洽商。

這類政治動盪可以說是泰國的標準。最近一次政變是1932年以來的第十二次,不但反映泰國內部政治陰謀的歷史,也顯示這個由在曼谷都市管治的精英和偏遠郊區政治影響力有限人口組成的多元社會,不時會發生衝突。泰國所以沒有四分五裂,全因佛教思想、強大的文化價值觀和對王室的尊敬所致。然而,一直令情況更混亂的,都是參與政治的泰國軍方,以及它各式各樣的商業聯盟,還有泰國在地緣政治中擠進緬甸、老檛、柬埔寨、馬來西亞和不太遙遠的越南和中國之間,需要機敏的地區外交手腕。

歷史上,泰國在自由討論社會、經濟和政治議題上,健康得令人意想不到。但是,在2014年政變後,媒體和互聯網都被監視和審查,大大減弱了此前所看到的開放思維。國家的嚴格叛逆罪一直被用作任何反對聲音的滅聲藉口,並通常加入另一個籍口,就是對國王及政治現狀構成壞影響。

開明思想在現代泰國歷史中植根。改革派暹邏國王蒙固(拉瑪四世)和朱拉隆功(拉瑪五世)於十九世紀歐洲土地擴張時所作的精明政治操控,讓暹邏沒有像其他亞洲鄰國落得成為殖民地的命運。泰國的外交蘊藏著像佛教一樣的「中間路線」,並洽談了各種結盟和條約,包括扭轉局面,但現在被認為不平等的貿易讓步:與英國於1855年簽定透過香港這個英國軍事/外交基地談判的《寶寧條約》,以及於十九世紀末至二十世紀初時把土地讓予法國人。與這些潛在歐洲反派合作,因為泰國領袖有意擁抱西方思想而緩和。朱拉隆功在位期間,真正推行了改革,見證了廢除奴隸制、改善衛生和基建,大幅革新政府行政,並討論引入君主立憲制度(最終於1932年實現)和民主。

與英國的友好關係確保泰國的傳統對頭緬甸因為英國的殖民版圖擴大而被壓制。同樣地,法國勢力擴展到中印半島(老撾、柬埔寨和越南)為北部和東部的對頭提供了另一層緩衝––特別是來自被削弱的中國。泰國本身也是英國和法國以及兩國殖民地之間的緩衝區,因此,泰國的外交很多時都反映了歐洲和世界政局的改變。這於冷戰時期尤為顯著,因為泰國近美國,讓美軍在國土上興建陸軍和空軍基地,在越戰期間用於多項炸彈和軍事行動。

泰國通常都被描繪成謎一樣的神秘國度;而佛教的彈性和靈性信俗可以容許很多令人意外的事情出現。作為恢復和諧的姿態––和諧素來都是佛教的意願––「想像和平」是一場由泰國文化部和曼谷都會政府在2010年暴力街頭抗議後舉辦的和解藝術展覽,展出多位泰國重要藝術家的作品,在描繪抗議行動和重新考慮動盪的政治和社會來源方面絕不手軟。

泰國政府部門舉辦這種可能政治敏感的藝術展覽實屬難得。在香港, 雨傘運動後的和解幾乎不存在,而官方的建立橋樑,至今在新的林鄭班子下只暫時有可能出現。這次展覽中其中一個可以看到的主要訊息,來自卡明.勒差普拉瑟。他複製了曼谷《國家報》標題為「曼谷在燃燒」的一頁,然後在該頁面上蓋上泰式骷髏骨頭圖案,並命名為:「要和平出現,我們必須殺死……自己心內的貪婪、憤怒和虛榮。」

這是普世準則,但香港的政治反對派應注意卡明.勒差普拉瑟的簡單忠告在和解前是必需的。那麼,伸出手來握手吧––因為要出現政府自發舉辦雨傘運動和解藝術展覽未免期望過高了!

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2017年11月11日。

A Thai Reconciliation Message

by John Batten

Political intrigue is a constant in Thailand, its presence a sort of secular undercurrent to the more obvious rhythms of Thai Buddhism and spirituality. Politics has for months, publicly at least, been largely put aside as Thailand mourned the death of King Bhumipol Adulyadej (Rama IX) that culminated in his elaborate public funeral ceremonies and private cremation a fortnight ago.

Thailand’s political upheavals in 2010 and 2013-2014 and violent street clashes between pro-government supporters (known as ‘Red Shirts’) of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his sister and then-incumbent Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, and anti-government protesters (known as ‘Yellow Shirts’) culminated in a military coup d’état led by Army Commander General Prayut Chan-o-cha in May 2014. Prayut suspended most parts of the Thai constitution and currently heads an unelected military junta. This is untenable, but is a holding position to keep the streets free of further protests. An election has been promised in November 2018, but with the military retaining ultimate power under a new constitution the return of civilian governance will surely be negotiated, undoubtably behind closed doors.

It could be said that such political unrest is the norm in Thailand. The most recent coup d’état is the twelfth since 1932 and reflects Thailand’s history of internal political intrigue and a diverse society comprising such groups as an urbanised Bangkok governing elite and a far-flung rural population with little political clout, that can – at times – clash. The country is held together by Buddhism, strong cultural values, and respect for the monarchy. Add into the mix, however, is the always politically-involved Thai military and its wide-ranging business alliances and Thailand’s pivotal geopolitical position wedged between Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia and a not-to-distant Vietnam and China requiring astute regional diplomacy.

Thailand has a surprisingly healthy history of free discussion on social, economic and political issues, but after the 2014 coup the media and the internet have been monitored and censored, blunting previous openness. Increasingly, the country’s strict lèse majesté laws have been used as an excuse to silence any opposition, often with the excuse that the monarchy or the political status quo have been maligned.

The origins of liberal thought are rooted in modern Thai history. Canny political maneuvering by the reformist Siam monarchs Mongkut (Rama IV) and Chulalongkorn (Rama V) in the face of European territorial expansion in the 19th-century allowed Siam to avoid colonization, the fate of a majority of its Asian neighbours. Thai diplomacy entailed both a Buddhist-like ‘middle way’ and negotiated alliances and treaties, including pivotal, but now-recognized as unequal trade concessions: to the British with (and negotiated through the British military/diplomatic base of Hong Kong) the Bowring Treaty of 1855 and territorial concessions to the French in the late 19th and early 20th century. Engagement with these potential European antagonists was tempered by the genuine willingness of Thai leaders to embrace Western ideas. During Chulalongkorn’s reign the implementation of reforms was real and saw the abolition of slavery, improved sanitation and infrastructure, a major overhaul of government administration and discussions to introduce a constitutional monarchy (eventually achieved in 1932) and democracy.

Friendly relations with the British ensured Thailand’s traditional rival, Burma, was neutralized by British colonial expansion. Likewise, the French expansion into Indo-China (Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam) offered another buffer from northern and eastern rivals – especially from a weakened China. Thailand itself was also a buffer between the British and French and their respective colonies – thus, Thai diplomacy often reflected the changing political situation in Europe and the world. This was seen most notably during the Cold War as Thailand aligned itself with the U.S.A., allowing the construction of U.S. army and air bases on Thai soil and used in bombing runs and military operations during the Vietnam War.

Thailand is often portrayed as enigmatic, a place of mystic; while Buddhist flexibility and spiritual beliefs can allow surprises. In a gesture to restore harmony – always a Buddhist aspiration - Imagine Peace was a reconciliation art exhibition mounted by the Thai Cultural Ministry and the Bangkok Metropolitan government just after the violent street protests of 2010. The exhibition, comprising Thailand’s major artists, pulled no punches in its depiction of the protests and reconsidered the political and social origins of the unrest.

It is remarkable that it was a Thai government agency that mounted such a potentially-sensitive political art exhibition. In Hong Kong, reconciliation after the Umbrella protests has been almost non-existent, and official bridge-building is only now tentatively happening under the new Lam administration. One of the fundamental messages seen in this exhibition was by artist Kamin Lertchaiprasert, who reproduced a page from Bangkok’s The Nation newspaper which had the headline “Bangkok Burning” emblazoned on it, the artist had then over-painted this page with a Thai-stylized skull, and entitled it: For peace to happen we must kill…greed, anger, vanity in ourselves first.

That is a universal maxim, but Hong Kong’s political antagonists should note that Kamin Lertchaiprasert’s simple admonishment is necessary before reconciliation. So, get your hands out and shake - for a government-initiated Umbrella reconciliation art exhibition would be expecting too much!

This opinion piece was first published in Ming Pao Weekly on 11 November 2017