藝評

Saigon in Hong Kong and the 'Napalm Girl' photo controversy

約翰百德 (John BATTEN)

at 4:34pm on 19th August 2025

Above image: The Associated Press' Nick Ut's iconic photograph, Napalm Girl, hanging in The Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong.

A version of this article by John Batten was first published in The Correspondent, the magazine of The Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong, July-September 2025 issue. In English only.

Saigon in Hong Kong and the 'Napalm Girl' photo controversy

by John Batten

A poignant time for many in South Vietnam and known as Black April or Tháng Tư Đen, the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon – 30 April 1975 – was celebrated with spectacular parades and fireworks celebrations in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) by the Vietnamese government. Meanwhile in Hong Kong, Saigon has always had a presence, both physically and in the city’s psyche - I'll cover some below.

Hong Kong's Foreign Correspondents' Club (known universally as the FCC) has a reputation as the world’s most famous press club. This was cemented during the Cold War; it was a haunt for journalists and news agencies covering the Vietnam War. In the FCC, all sorts of 'China watchers' mingled with journalists, businesspeople, and visitors passing through Hong Kong and debated the merit of rumours during the Cultural Revolution. Later, waves of Vietnamese refugees sought escape through Hong Kong.

Hong Kong film director Ann Hui On-wah made three films about the experiences of Vietnamese illegal immigrants. In her landmark Boat People (1982), she chronicled the persecution experienced by those living in South Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon, showing the political and social conditions that led many to flee Vietnam.

Since Black April, I’ve looked around Hong Kong discovering Saigon in the city. It’s here in pockets. Of course, if you live in or visit Sai Kung, then you are in 西貢, the same Chinese characters as Saigon.

Tai Kok Tsui has its streets named after trees, and a small locale in Yau Ma Tei and Jordan has streets and roads named after cities: Shanghai, Canton (1), Nanking, Ning Po – and, Saigon Street bisects the two districts. The area retains, despite development, traditional restaurants, pawn shops, repair places, street stalls, fruit vendors, all types of Nepalese businesses and the overflow of Temple Street’s market vibrancy. I hoped to find a Vietnamese restaurant or a pho noodle-shop on Saigon Street, but there aren’t any. However, the Yau Tsim Mong Multicultural Activity Centre, mid-point on Saigon Street, did have “Vietnamese Fruit Holders” for sale, small ceramic and woven baskets that can also hold keys, we are helpfully advised.

If you walk to the Jordan end of Saigon Street and arrive at Ferry Street, you are close to Tim Kee French Sandwiches (30 Man Yuen Street, Jordan). “The best Vietnamese bahn mi in Hong Kong,” a customer told me as I entered the small hole-in-the wall shop that has been serving traditional baguette, pâté and pickled salad for 25 years – all with a hint of pepper hotness. He told me he had driven from Sai Kung just for the baguette; I made the obvious joke: “You drove all the way from Saigon for a Vietnamese sandwich!”

Preparing another Vietnamese sandwich at Tim Kee French Sandwiches in Jordan, Kowloon (photo: John Batten)

At the other end of Saigon Street, near Diocesan Girls’ School, I walked the staircase to the top of an old tong lau, a walk-up terrace building, built in the late 1950s. On top, there were the ruined outlines of rooftop flats and a food factory, with the leftover rusty skeleton of supports for a chimney. With a long view down Saigon Street, the rooftop is now devoted to clotheslines and lots of chairs for the occasional BBQ. A friend of mine, Rinnie, her mother and sister, Chinese Cambodians, had lived atop similar in the 1990s.

Hanging washing on the rooftop of a tong lau on Saigon Street, Jordan (photo: John Batten)

Remnants of a food factory chimney on the rooftop of a tong lau, with a view overlookng Saigon Street, Jordan (photo: John Batten)

On 17 April 1975 the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh, ending the Cambodian civil war. The city’s populace were forced from their work, homes and businesses “into the countryside” and opposition troops were rounded-up and executed. The madness of the Khmer Rouge regime saw millions die of starvation, illness and violence in the following years. Rinnie and her family escaped, like many others, by walking from Phnom Penh to Saigon. Still a young girl, her overriding memory is of dead bodies lining the sides of the road. Her scattered family, a classic Southeast Asian Chinese diaspora family, operated small businesses in Yangon, Saigon, Hong Kong, whilst also having relatives in Guangzhou. Eventually, they were able to resettle through family reunion in Hong Kong, living for a time in a small Causeway Bay rooftop flat, not much different from this Saigon Street rooftop.

Rinnie walked along Route 1, the main road from Saigon to Phnom Penh. On the same road on 8 June 1972, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, her brother, grandmother and cousins, fled napalm fire-bombing by the South Vietnamese air force trying to disperse Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops from Trang Bang village, 60 kilometres from Saigon.

Caught in the bombing and badly burnt, Kim Phuc had taken off her burning clothes and ran with her family down the road as the village burned behind. A group of photographers and TV cameramen were ahead of the children, also on the road. The iconic photograph ‘The Terror of War’ or ‘Napalm Girl’ was taken by one of them. Published the following day in the New York Times and the LA Times amongst others, it was subsequently republished around the world. The Associated Press (AP) photographer Huynh Cong ‘Nick’ Ut won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 and a World Press Photo award for the photograph. (2)

The Associated Press' Nick Ut's iconic photograph, Napalm Girl, hanging in The Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong. (2)

Shown at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival, an investigative documentary film, The Stringer, directed by Bao Nguyen, questioned who took the iconic photograph. Carl Robinson was the photo editor working in the AP Saigon bureau office at the time and alleges that he was told by Horst Faas, AP’s head of photography, to change the named attribution of the photograph from a stringer (3) to the AP photographer Nick Ut. That stringer is identified in the film as Nguyen Thanh Nghe, who was assisting an NBC TV crew as a driver on the day, and says he also shot a roll of film and delivered it to the AP bureau office, hoping to sell one of his own freelance photographs. Finally, the film analyses the relative physical positions of all the photographers, including the stringer, working on that day from the available evidence, claiming that Nick Ut was not in position to take the photograph.

In early May 2025, Associated Press released its own comprehensive analysis. (4) In summary, it maintains the attribution of Nick Ut as author of the photograph, but concedes there is doubt, stating that “probably Nick Ut took the photograph.”

Correspondent Laura Westbrook and I, edited by Jarrod Watt, have made a podcast, (5) available on the FCC website, discussing the photograph and complexities of the film’s allegations. We all await to see The Stringer, but the film’s producers have not released it yet for general distribution.

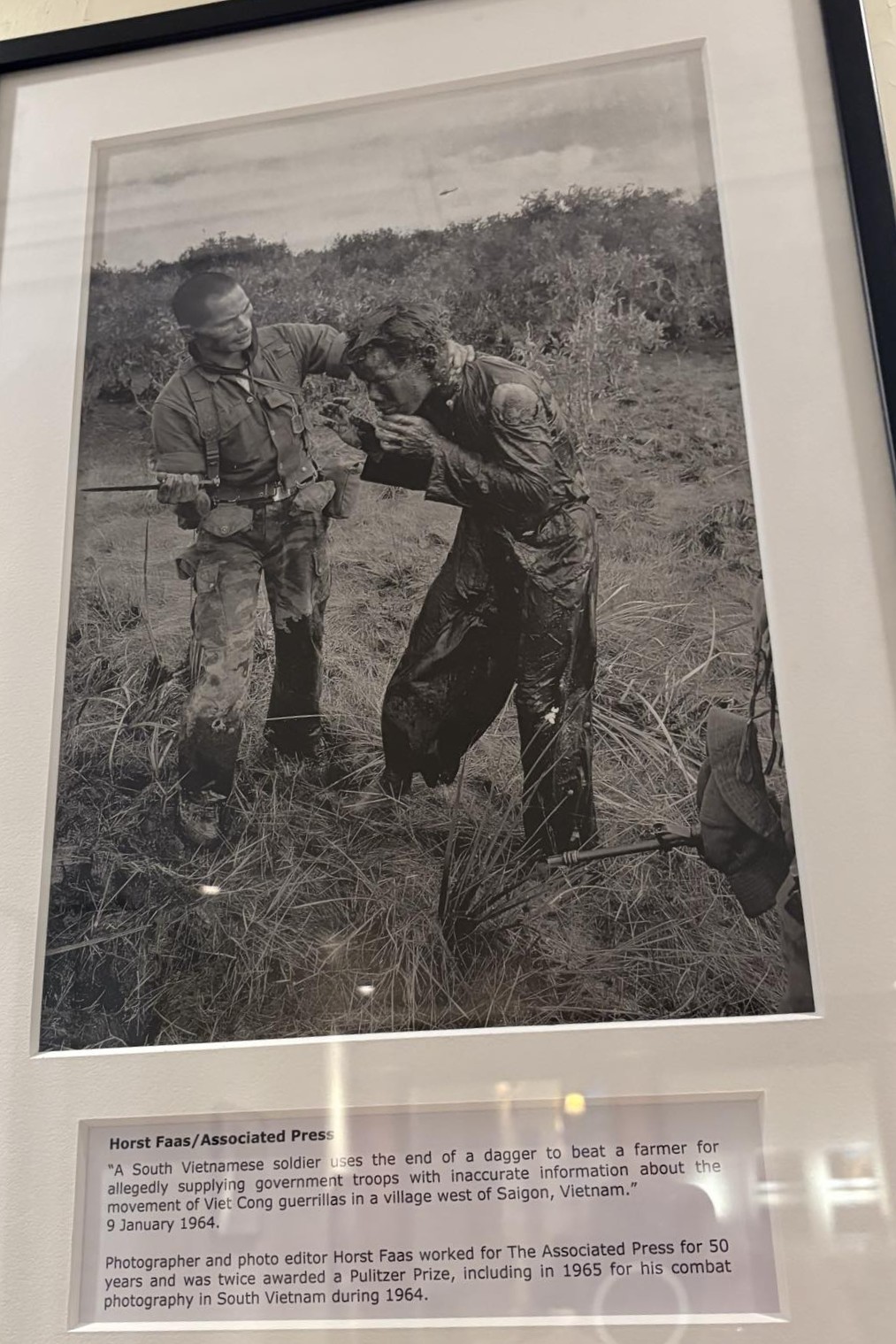

Nick Ut’s signed ‘Napalm Girl’ photograph can be seen in the FCC Bunker. It hangs alongside other distinguished Vietnam War photographs. Horst Faas was AP’s chief photographer for Southeast Asia based in Saigon for over ten years and two of his most harrowing, brutal photographs are on the wall: a drawn dagger as a mud-covered farmer is threatened with death for allegedly giving false information; and, above it hangs a photograph of a road covered with bodies. Likewise, photographer and longtime Hong Kong resident Hugh Van Es’ nearby photographs depict the dire battle conditions on infamous Hamburger Hill.

One of the Associated Press' Horst Faas' iconic Vietnam War photographs hanging in The Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong.

In the 1960s, LIFE magazine had a shelf-life much longer than its week of publication: for months, past copies would sit in doctor and dentists’ waiting-rooms, it was ubiquitous in barber shops; copies were seen in school class-rooms and then cut and pasted in art rooms. Read by millions around the world, LIFE’s long photo essays and text were highly influential – especially about the Vietnam War.

Also in the Bunker are photographs by Larry Burrows from his long photo essay One Ride with Yankee Papa 13. Burrows spent a day, 31 March 1965, on the U.S. helicopter Yankee Papa 13, with its crew on a combat operation to support soldiers on the ground under attack from the Viet Cong. Published a fortnight later in LIFE, the visceral and sudden violence of the mission resulted in one dead and another crew member seriously injured. Burrows was in the middle of the action and his photographs, of the blood, fear, anguish and the crew’s emotional return to base, were published – shocking and uncensored – for LIFE’s readership.

Two of Larry Burrow photographs from his long photo essay One Ride with Yankee Papa 13, published in LIFE magazine, 1965.

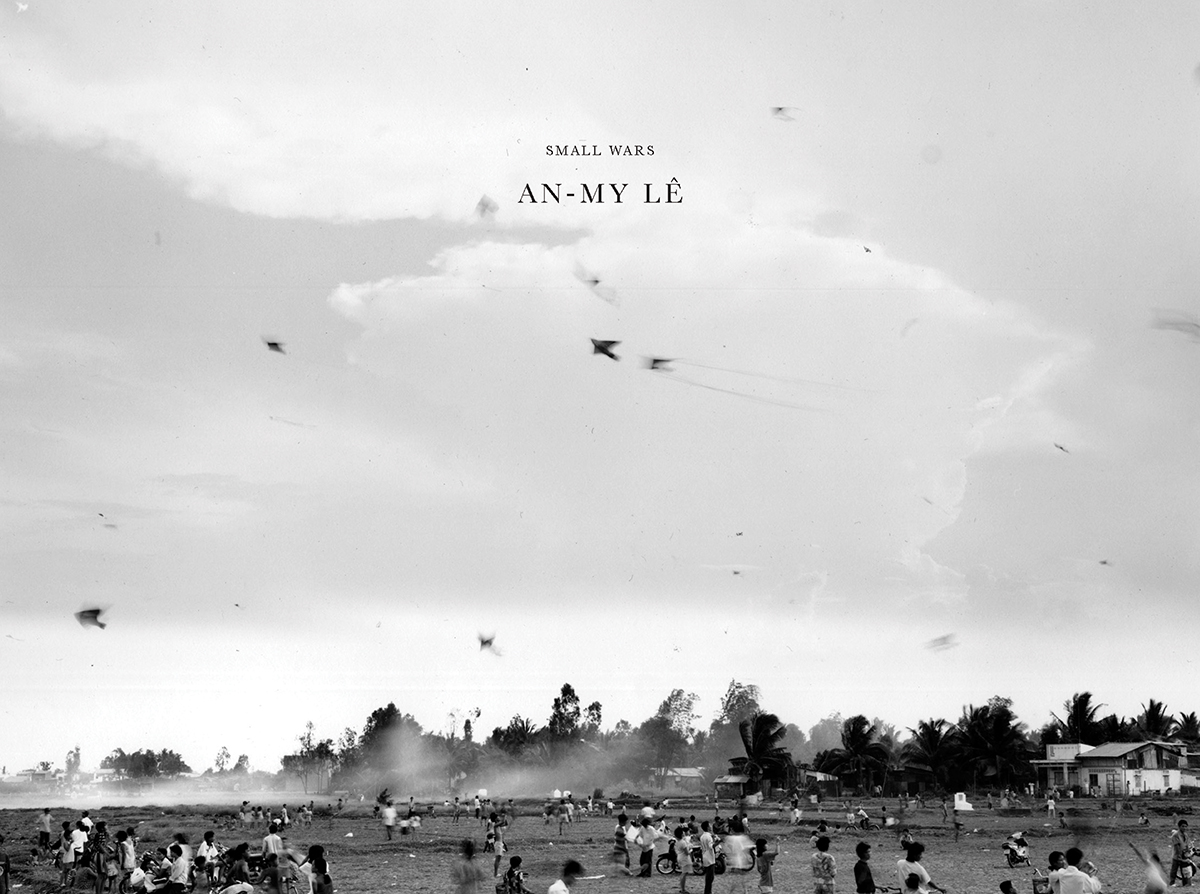

In contrast, American-Vietnamese photographer An-My Lê’s photobook Small Wars (2005) shows two aspects of the aftermath of the war. In beautiful large-format prints to be republished as a 20th anniversary edition, she depicts a calm but battle affected Vietnam, both in the countryside and cities. In the second section of her book, she photographs returned American veterans re-enacting the violence of Vietnam War battles in the U.S., using authentic weapons, vehicles, uniforms, flares, lighting and battle locations similar to those found in Vietnam. In some photographs, the photographer has agreed to dress and act as a Viet Cong guerilla, replicating their infiltration amongst the wet forests of the Mekong Delta. This is ironic: Lê herself is a former refugee who escaped from Vietnam.

The cover of An-My Lê’s photobook Small Wars, originally published in 2005; a 20th anniversary edition has now been published by Aperture.

Found around Vietnam’s many rivers and forest areas, the distinctive green Chinese Water Dragon is, despite its name, not common in China. Poached in Vietnam for its meat and as a popular pet for the illegal pet trade, the water dragon and its eggs are also added to Vietnamese rice wine, supposedly for extra male potency. A pair can be seen in the Tuen Mun Park Reptiles House and the species is reportedly feral in Hong Kong’s country parks.

A pair of Chinese Water Dragons at Tuen Mun Park Reptiles House, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong (photo: John Batten)

I can’t imagine drinking lizard infused rice wine, but Vietnam Lemonade is a refreshing summer mocktail and easy to make at home. Adding gin or vodka gives it bite as a cocktail.

Vietnam Lemonade Ingredients:

1 pc - lemongrass stalk

5 pcs - Kaffir lime leaves

15ml - fresh lime juice

10ml - sugar syrup

1 drop - fish sauce

1 cinnamon stick to garnish

Add chopped lemongrass stalk and lime leaves into a cocktail shaker, give it a good muddle. Add all the other ingredients and fill with ice and shake hard. Strain into a highball glass and top-up with soda. Add vodka or gin to your liking for a cocktail.

So... "Cheers!" Or, as they say in Vietnam: “Một hai ba, dô!” – “One, two, three, go!”

References & links:

(1) Canton is both the former English name for the city of Guangzhou and for the province of Guangdong. To be precise, the signage for Canton Road in Yau Ma Tei is actually - if reading the Chinese characters - referring to Guangdong, the province and not the city.

(2) Visitors may visit The Foreign Correspondents' Club Hong Kong during office hours to see these photographs in the Bunker, a small room next to the ground floor Main Bar - visitors must first register at Reception.

(3) A 'stringer' or 'fixer' is a freelance worker employed by journalists and press agencies to undertake a variety of tasks to help in their work: translation, deliveries, driving, finding interviewees, find locations for photographers to shoot, etc.

(4) The full Associated Press ‘Napalm Girl’ report, May 2025, can be read here:

TerrorOfWarReportUpdate_May2025.pdf

(5) The FCC Podcast with John Batten & Laura Westbrook discussing the 'Napalm Girl' photo controversy can be listened here:

https://open.spotify.com/episode/5X62zV2UaU92fCoU7udb1p