藝評

‘Expressionists’ and ‘Now you see us’: two Tate exhibitions during the summer of 2024

祈大衛 (David CLARKE)

at 12:15pm on 20th September 2024

(A review of two exhibitions at the Tate, London by Dr David Clarke, in English only)

Above image:

Gabriele Münter, Murnau Farmer’s Wife with Children, 1909–1910. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957 © DACS 2024

Exhibition review:

‘Expressionists’ and ‘Now you see us’: two Tate exhibitions during the summer of 2024

by David Clarke

It would be fairly uncontroversial to describe Paris as the leading artistic capital of the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. Not only did French artists tend to converge on their country’s capital city, but many artists from elsewhere found their way there too. Artists as various as Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Marc Chagall (1887-1985) and Xu Beihong (1895-1953) all spent time in Paris. Nevertheless, there were other European cities that were significant artistic centres during this period too. Vienna would be one example, as would Munich. The Tate Modern exhibition, ‘Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider’ (25 April – 20 October 2024) presents art from that latter city in the south of Germany, a great many of which are on loan from Munich’s Lenbachhaus.

I find the title ‘Expressionists’ potentially a bit misleading, since it suggests a wider coverage than the exhibition provides. The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) was indeed one of the two most significant groups in German expressionism, but there is much else as well. The other main group, The Bridge (Die Brücke), belongs to an earlier period, and to different urban centres. It was formed in Dresden in 1905, and can also later be associated with Berlin, to which leading member Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) moved in 1911. It was a more closely-knit grouping than the Blue Rider. Although the term ‘Expressionism’ has become closely associated with German art, in fact much other art of the early twentieth century could just as accurately be described as expressionist. That of the French Fauve artists such as Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) could certainly be characterized by that term, and at one point its use was considered for employment in relation to the 1910 London exhibition organized by Roger Fry (1866-1934) and eventually named ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’. Certainly a ‘Post-Impressionist’ artist such as Van Gogh was deeply concerned with expressive goals in his art.

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation Deluge, 1913. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

The emphasis of the exhibition is on Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Gabriele Münter (1877-1962), as its subtitle indicates. It includes works from before and after the period of the Blue Rider group itself, which had only a short existence from 1911 to 1914. Kandinsky is clearly one of the major artists of the twentieth century, and one of the pioneers of abstract art. Improvisation Deluge of 1913 belongs to the period when abstraction was emerging in his painting, while Riding Couple of 1906-1907 - also included in the exhibition - is one of the more interesting works from the years prior to that stylistic transformation. However, to single these two artists out from the larger group who were associated with the Blue Rider doesn’t seem quite appropriate. Along with most other female artists Münter has been underestimated in the larger narrative of art history, but I feel the prominence she is given in this exhibition is unwarranted. Many of her photographs are included - some of which have only been printed in recent years rather than during the artist’s lifetime - and in my opinion they have only limited aesthetic value. I find her artistic contribution considered as a whole (and represented in the exhibition by works such as Murnau Farmer’s Wife with Children of 1909–1910) to be less original than that of several other artists associated with the Blue Rider group, such as Franz Marc (1880-1916). Marc and Kandinsky were the two editors of the Blue Rider Almanac which appeared in 1912, and he is central to the story of the group right from its beginnings. Also, less prominently featured in the exhibition is August Macke (1887-1914), who like his friend Marc was to die during the First World War. Both are artists who developed highly distinctive styles in their relatively short lives, and while there are significant works by them in this exhibition (such as Marc’s Tiger of 1912) these are relatively few in total. Perhaps less central to the Blue Rider (he only participated in the second of their two exhibitions), but nevertheless perhaps the only other artist featured here of equal historical significance to Kandinsky, is Paul Klee (1879-1940). The marginal placement in the exhibition of this major artist - widely influential through his pedagogical writings which other leading European modernists such as Matisse and Picasso did not produce counterparts to - is hard to understand.

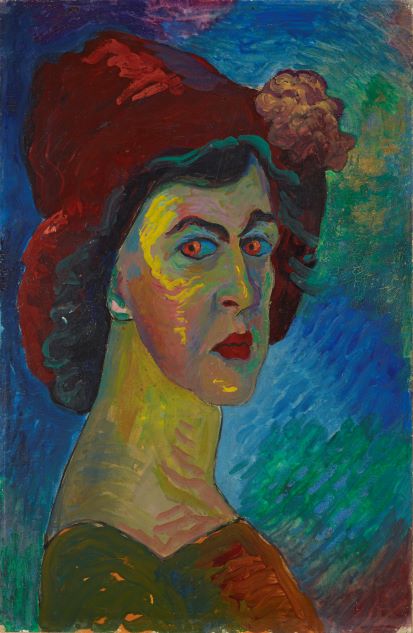

.jpg)

Franz Marc, Tiger, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of the Bernhard and Elly Koehler Foundation 1965

If these important artists are in my opinion underrepresented in the exhibition, several other artists normally considered minor figures in the Blue Rider story are given a relative prominence. A particular aim of the exhibition seems to be a recovery of the contribution by female artists, and apart from Münter the most significant of these is Marianne von Werefkin (1860-1938), represented by such works as Self-portrait I of c.1910. A Russian artist from a privileged background (Münter was also independently wealthy), she had studied with the realist painter Ilya Repin (1844-1930), who painted her portrait in 1888. For a long period she was in a relationship with Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941), who is also represented in the exhibition, and for a not inconsiderable part of that time she put aside her own artistic endeavors to nurture his development as a painter. Less significant that Werefkin and Münter in my view are two other female artists included in the exhibition, Elizabeth Epstein (1879-1956) and Maria Franck-Marc (1876-1955). A work by Franck-Marc in ‘Expressionists’ is Girl with Toddler of c.1913.

Marianne von Werefkin, Self-portrait I, c.1910. Lenbachhaus Munich

Maria Franck-Marc. Girl with Toddler, c.1913. Lenbachhaus Munich. © Legal succession of the artist

Rather more successful in recovering for the historical record the contribution of female artists is an exhibition which took place concurrently to ‘Expressionists’ at Tate Britain, ‘Now you see us: Women artists in Britain 1520-1920’ (16 May - 13 October 2024). More than just a display of items from the Tate’s own collection, this is a comprehensive survey involving many loans and revealing significant artworks by an extensive range of female artists - many of whom have not previously received the broader exposure they deserve. Over 100 artists are featured.

Towards the start of the exhibition we are introduced to one of the most famous female artists of all time, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1656). A self-portrait in which she shows herself engaged in the act of painting is on display, as well as her Susannah and the Elders. Both are loaned from the British Royal Collection. Well known in her own lifetime for her art, Gentileschi lived in various locations including Florence, Rome, Venice and Naples. She had learned to paint in the studio of her father Orazio Gentileschi (1563-1639), who had been deeply influenced by Caravaggio (1571-1610). Her father had arrived in England in 1626, spending the rest of his life there, and she came to London around 1638-1639 to join him not long before his death. Many of her paintings are on themes that prominently feature female figures, and in that respect Susannah and the Elders is typical. It tells the Old Testament story of a woman facing sexual assault from two male authority figures, who falsely accuse her of adultery when she resists them. Painted c.1638-1640, it originally hung at Whitehall Palace in the Withdrawing Chamber of Queen Henrietta Maria, its likely patron. This was not the first time Gentileschi had painted the theme – her earliest surviving work (completed in 1610 when she was only 17) treats the same subject. The poses of the three figures are different in this later version – it was not simply a matter of producing a copy of her earlier effort.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, c.1638-1640. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Angelica Kauffman, R.A, Colouring, 1778-80 © Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photographer: John Hammond

Another foreign-born artist featured in the exhibition - who spent a much longer part of her life in Britain than Gentileschi - is Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807). Swiss-born, Kauffman spent time in Italy, where she made contacts with British visitors, and this led to her moving to England in 1766 (although at the end of her life she was back in Rome). One of the first two female members of the Royal Academy of Arts - which was founded in 1768 - she became close to Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), its first president. Paintings she produced for the ceiling of the Royal Academy’s Council Chamber are featured in the exhibition. Invention (1778-1780) and Colouring (1778-1780) are two of the four allegorical roundel paintings that had been commissioned from her on the theme of ‘Elements of Art’. Amongst other paintings by Kauffman included in ‘Now you see us’ is a self-portrait dating to c.1770-1775. She represents herself as an artist in this canvas by showing herself holding tools of her trade, but the flavour is quite different from the Gentileschi self-portrait (an allegory of ‘painting’). Whereas Gentileschi offers a side view of a figure actively engaged in her work on a canvas, Kauffman gives us a three-quarters view of a figure consciously presenting herself to the viewer, whose gaze she meets.

Female artists active in England in the century prior to Kauffman were primarily involved with portraiture, which of course remained a major source of income for painters in the eighteenth century too, despite the opportunities for showing works in exhibition which were by then beginning to emerge. Amongst those from the seventeenth century featured in ‘Now you see us’ are Mary Beale (1633-1699) and Joan Carlile (1606-1679). Another portrait painter from a slightly later date was Maria Verelst (1680-1744). Only a few paintings survive by Anne Killigrew (1660-1685), but she was able to venture beyond the genre of portraiture as her Venus Attired by the Three Graces (c.1680) demonstrates. This short-lived artist (who was also a poet) had family connections to the Stuart court, and indeed a portrait of James II (from 1685) is amongst her surviving works.

A largely chronological structure is adopted in the organization of the displays in ‘Now you see us’, taking us from the first half of the sixteenth century all the way to the early twentieth century. At the chronological end point of the exhibition we meet artists as varied as Laura Knight (1877-1970), Vanessa Bell (1879-1961) and Gwen John (1876-1939). Knight was relatively unaffected by modernist trends, but Bell belonged to the Bloomsbury Group and had an engagement with continental artistic developments. With fellow Bloomsbury Group artist - and sometime lover - Duncan Grant (1885-1978) she created the Famous Women Dinner Service (1932-1934), a set of 50 hand-decorated dinner plates commissioned by art historian Kenneth Clark (1903-1983). Since the analogous but much more famous The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago (b. 1939) dates to 1979, it was something of a pioneering effort in celebrating historic female achievement through art.

.jpeg)

Gwen John, Self-Portrait, 1902. Photo Tate (Mark Heathcote and Samuel Cole)

John had studied at the Slade School of Art in London, at that time the only British art school accepting female students. She also studied with James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) in Paris. She spent much of her adult life in France, where she was for a period in a romantic relationship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). John primarily engaged in portraiture - a genre which preoccupied many of the earliest artists featured in this exhibition, but which for her would have been a conscious choice rather than an economic necessity. Her Self-Portrait of 1902 is markedly different from both the Gentileschi and Kauffman self-portraits previously discussed, demonstrating how this genre has evolved over time. Johns has clearly a greater interest in expressing interiority, and shows almost no concern for social role. In John’s own lifetime her reputation was overshadowed by that of her younger brother Augustus John (1878-1961), who had also studied at the Slade and whose art was much acclaimed. With time her contribution has come to be better understood, while her brother’s reputation has somewhat faded.

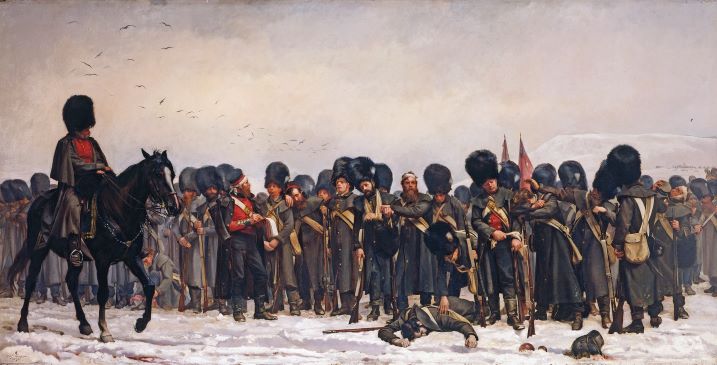

A diversity of subject matter not possible for earlier female artists is seen in the work of their nineteenth and twentieth century counterparts. Elizabeth Butler (1846-1933), who is known for her battle paintings, is represented by Calling a Roll after an Engagement, Crimea (1874), for instance. French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), famous in her own time for her images of animals, is represented by Sheep in the Highlands (1857), one of the works which resulted from a trip she made to Scotland. Exploration of media beyond oil paint is demonstrated by the prominent watercolourist Helen Allingham (1848-1926) and the photography pioneer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879).

Elizabeth Butler, The Roll Call, 1874. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Diversity of other kinds is permitted by the inclusion of Jewish artist Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886) and American-born artist Anna Lea Merritt (1844-1930). Merritt’s Love Locked Out (1890) is a naturalistic image of Cupid viewed from behind, outside the locked door of a tomb. This became the first work by a female artist to enter the Tate collection (as part of the Chantrey Bequest). It had been painted by Merritt in memory of her husband, who had died in 1877, only a few months after their marriage.

Arguably a more overt diversity is given to ‘Now you see us’ by the inclusion of a painting by openly lesbian artist Clare Atwood (1866-1962). She is represented in the exhibition by The Terrace outside the Priest’s House (1919), which depicts the place where she herself lived in a ménage à tois with two other women, writer Christabel Marshall (1871-1960) and theatre director and producer Edith Craig (1869-1947). All three are seen together in this painting. Like John, Atwood had studied at the Slade School of Art. Prominent in her output are a number of paintings concerning the First World War, painted both at the time of the war itself and after. Some of these are in the collection of London’s Imperial War Museum, which had commissioned them in 1920. Although Rosa Bonheur (perhaps the most famous female artist of her era) never explicitly called herself a lesbian (unlike Atwood), she almost certainly was. She adopted male dress, and had close relationships with females rather than marrying.

Ethnic diversity enters the exhibition via Solomon’s A Young Teacher (1861), which uses a Jamaican-born female model to represent the only adult in the painting. Two female children are shown with a book. The younger one gazes at it, while the older one points towards something in it. The adult (who holds the younger child in her lap, and has the other’s hand on her shoulder) is however looking out towards the right side of the painting, as if perhaps showing awareness of a presence unseen by us.

I feel ‘Now you see us’ does a better job of representing diversity than ‘Expressionists’ since it only treats ethnic difference or questions of sexual orientation when those issues arise in the works themselves. In ‘Expressionists’ one sometimes feels that the wall texts are focusing more on issues that may be considered significant in our own era (such as those surrounding gender identity), rather than discussing the works in terms that would have made sense to the artists themselves.

Rebecca Solomon, A Young Teacher, 1861. Tate and the Museum of the Home

Two exhibitions at Tate, London, United Kingdom:

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider (Tate Modern, 25 April – 20 October 2024)

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 (Tate Britain, 16 May – 13 October 2024)