Reviews & Articles

When Much More Than Three Books Meet – Serendipity, Possibility

Yang YEUNG

at 5:41pm on 11th November 2011

(原文以英文發表,題為《豈止是三本書的相遇 - 其偶發性與可能性》。)

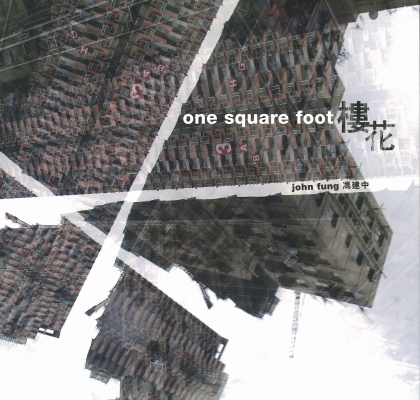

When John Fung first showed me a photograph of the many now collected in his newly published book One Square Foot, we were considering making an exhibition of them. I was profoundly affected - one piece, such force.

I shared my response with him in an email. “How can one trust photography today?” I wrote. “What is it that is demanded from us, if not skepticism around the easy question of real and fake, genuine or copy, art or craft? And trust? What is it anyway? Total urbanization may be a jargon for some, but not your works – they pitch not conceptual games, but approach physical violations upfront; violence even, that bear marks of bull-dozers-driven development (destruction?). The imperative to ask ‘What is behind the veil of prosperity?’, ‘What are the limits of skyward thinking?’, ‘What kind of jungle is our lives caged in?’ is activated in order to rebel, indeed, but also, more importantly, to ask, ‘How are you feeling today?’”

Now, as more than seventy photographs come together in a book published by MCCM Creations that measures one square foot, they “pack a punch”, says John Batten in his essay “Repeat: 1968/2001/2006”. Four more essays by writer Su Hei, artist Lo Yin Shan, architect Alvin Yip, and poet Madeleine Marie Slavick were collected and bound on the inside of the one square foot as a smaller black and white attachment, waiting to be flipped and found – a clever and measured editorial and publishing decision of placing what could have been texts that overwhelm the voice of his works; not that they are better or worse, but that each thump of their silent screams for the humanitarian and humane betray the suspicion that Fung also finds himself caught. Jean-Francois Lyotard articulates this suspicion as a double treatise in Inhumanity published in 1988. “What if,” he says, “human beings, in humanism’s sense, were in the process of constrained into, becoming inhuman (that’s the first part)? And (the second part), what if what is ‘proper’ to humankind were to be inhabited by the inhuman?” In the context of Fung’s book, a translation of Lyotard’s question could be, “Are not those who built the skyscrapers human, too?”

This leads to the second thoughtful decision the publisher has made. The size of One Square Foot corresponds to its title – it measures one square foot. Walk along a middle-class residential area in Hong Kong, say Mid-levels, one square foot is for sale at six to eight thousand Hong Kong dollars. One square foot in the property market scorches the hands, too hot to be held. In a book form, one square foot is substantial, expansive, concrete. It’s real.

Fung’s book was recently launched in Hong Kong with another two books. One of them is Flatness Folded – a collection of 23 contemporary Chinese garments by Miranda Tsui, which offers a different take on the book as object. Tsui’s book is jacketed with an opaque pattern cutting paper, but not entirely. A brim of the fabric cover page inscribed with the title is allowed to show.

It reminds me of a curious story in The Coming of the Book by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin about the title page in the Western history of books that made its debut at the end of the 1480’s. The story goes that manuscripts copied by the hand had no title page, hence its first leaf on the recto (right side of page) tended to soil. The printers then conceived the idea of starting the text on the verso, leaving the recto blank. Then, “from a quite natural desire to fill in the blank, they printed a short title on it and this helped to identify the book.”

It is not difficult to notice the care in designing the cover of Tsui’s book that inherits partly the transformation from the title-less book of the past to the title-prominent one in our present, while delivering a different story in between, precisely consistent with the message the book carries – fashioning the body as not just to show but also to not show. Considering the Prada high heel disaster, which Fashion Director of Telegraph.co.uk Hilary Alexander describes as “cruel and unusual practice, which must rival foot-binding in its blind indifference to comfort and safety?” (Sept 24, 2008), the collection in Tsui’s book that collects not signatures and height, but flatness and comfort, is quite a fashion manifesto in itself. Several years ago, Tsui created a video work called Shoe Stories. It shows images of shoes in blue and grey tones. Narrated by their many wearers, the work is a celebration of friendship between those who walk and their shoes. It is about walking, crossing paths, life paths. When what is everyday flatness is folded, it comes alive.

A lot of care was also given in designing Gary Chang’s My 32m2 Apartment – a 30-year transformation. It is light and in a horizontal grid, also flatness folded, not immediately hugging the body, but offering the home-dwelling safety and adventure at the same time. While explicitly autobiographical and documentative as a book that describes Chang’s apartment he had lived and transformed a large part of his life, it also exudes a strong sense of jumpy mischief, as if between the pages, a genie dances and plays hide and seek. Eric Wear suggests in his essay “Beyond compromise: a supple architecture for desires”, that Chang’s apartment opens like a book, or an accordion. Wear’s celebration of a book as an object designed to be a total world folding in, while ready to fan out its rhythm, is a tasteful one: firm and soft-spoken.

MCCM Creations is a small publisher based in Hong Kong. In November this year, it made the rare move of launching these three books in one go - rare, because Mary Chan who founded the publishing house has no appetite of personal fame; she had rather attribute attention and publicity to serendipity. “Never,” MCCM says in its book launch announcement, “have we thought three books would be released at once.” Rare also, because the very arrival of the three books was contemporary to the times when the form of the book itself is seriously questioned.

I am thinking of a forwarded email I (and perhaps many readers, too) received early this year calling for contribution to The Last Book project. It was sponsored by the National Library of Spain and curated by Luis Camnitzer. The curatorial statement says “the premise of the project is that book-based culture is coming to an end.” Hence, it sets out to “compile written as well as visual statements in which the authors may leave a legacy for future generations.” As I write, the curator has announced that the exhibition is scheduled to open on Nov 18, 2008. In Hong Kong, a contemporary art exhibition several months ago called *bōk- carries the sub-title “book review in this bookless age”.

How then, is the celebration of the arrival of new books to be understood? I remember a course on book design I was invited to co-teach. I was responsible for suggesting directions on the cultural and philosophical meanings of the book as a designed object. In the first class, I distributed to students lines from the dedication pages I copied from different books. My favourite ones include that of Paul Monette’s Becoming a Man – Half a Life Story. His dedication says, “For my brother who's walked the tallest of us all / And for Winston who keeps me dancing even in the dark.” Sadie Plant’s dedication was soulfully written, too. In zeros + ones, Digital Women + The New Technoculture, it says, “To all the contributory factors”.

I wanted these student designers to begin from treating the book as a gift that makes no demand on the benefactor for reciprocal returns. It is a gift from an elsewhere the reader never knows but is invited to appreciate as a guest with no obligations. I wanted them to notice faces of strangers always already inscribed in every book. Perhaps it is when the host disappears from what he/she has so hospitably hosted that his/ her skills are at their best, and the guests, the most at ease, the most comfortable.

When Fung says, “To my father, mother…and all parents,” and when Tsui says, “In memory of my grandmother Xie Zhan Yun, who taught me how to sew,” one finds any declaration of the first and the last quite irrelevant – each book is a home return to a vast world, dotted with silent voices that hew out the nuances of its many sides. I tend to think, as long as the world is recognized, books are not ready to die.

First published in Singapore Architect Issue 248, 2008.

When John Fung first showed me a photograph of the many now collected in his newly published book One Square Foot, we were considering making an exhibition of them. I was profoundly affected - one piece, such force.

I shared my response with him in an email. “How can one trust photography today?” I wrote. “What is it that is demanded from us, if not skepticism around the easy question of real and fake, genuine or copy, art or craft? And trust? What is it anyway? Total urbanization may be a jargon for some, but not your works – they pitch not conceptual games, but approach physical violations upfront; violence even, that bear marks of bull-dozers-driven development (destruction?). The imperative to ask ‘What is behind the veil of prosperity?’, ‘What are the limits of skyward thinking?’, ‘What kind of jungle is our lives caged in?’ is activated in order to rebel, indeed, but also, more importantly, to ask, ‘How are you feeling today?’”

Now, as more than seventy photographs come together in a book published by MCCM Creations that measures one square foot, they “pack a punch”, says John Batten in his essay “Repeat: 1968/2001/2006”. Four more essays by writer Su Hei, artist Lo Yin Shan, architect Alvin Yip, and poet Madeleine Marie Slavick were collected and bound on the inside of the one square foot as a smaller black and white attachment, waiting to be flipped and found – a clever and measured editorial and publishing decision of placing what could have been texts that overwhelm the voice of his works; not that they are better or worse, but that each thump of their silent screams for the humanitarian and humane betray the suspicion that Fung also finds himself caught. Jean-Francois Lyotard articulates this suspicion as a double treatise in Inhumanity published in 1988. “What if,” he says, “human beings, in humanism’s sense, were in the process of constrained into, becoming inhuman (that’s the first part)? And (the second part), what if what is ‘proper’ to humankind were to be inhabited by the inhuman?” In the context of Fung’s book, a translation of Lyotard’s question could be, “Are not those who built the skyscrapers human, too?”

This leads to the second thoughtful decision the publisher has made. The size of One Square Foot corresponds to its title – it measures one square foot. Walk along a middle-class residential area in Hong Kong, say Mid-levels, one square foot is for sale at six to eight thousand Hong Kong dollars. One square foot in the property market scorches the hands, too hot to be held. In a book form, one square foot is substantial, expansive, concrete. It’s real.

Fung’s book was recently launched in Hong Kong with another two books. One of them is Flatness Folded – a collection of 23 contemporary Chinese garments by Miranda Tsui, which offers a different take on the book as object. Tsui’s book is jacketed with an opaque pattern cutting paper, but not entirely. A brim of the fabric cover page inscribed with the title is allowed to show.

It reminds me of a curious story in The Coming of the Book by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin about the title page in the Western history of books that made its debut at the end of the 1480’s. The story goes that manuscripts copied by the hand had no title page, hence its first leaf on the recto (right side of page) tended to soil. The printers then conceived the idea of starting the text on the verso, leaving the recto blank. Then, “from a quite natural desire to fill in the blank, they printed a short title on it and this helped to identify the book.”

It is not difficult to notice the care in designing the cover of Tsui’s book that inherits partly the transformation from the title-less book of the past to the title-prominent one in our present, while delivering a different story in between, precisely consistent with the message the book carries – fashioning the body as not just to show but also to not show. Considering the Prada high heel disaster, which Fashion Director of Telegraph.co.uk Hilary Alexander describes as “cruel and unusual practice, which must rival foot-binding in its blind indifference to comfort and safety?” (Sept 24, 2008), the collection in Tsui’s book that collects not signatures and height, but flatness and comfort, is quite a fashion manifesto in itself. Several years ago, Tsui created a video work called Shoe Stories. It shows images of shoes in blue and grey tones. Narrated by their many wearers, the work is a celebration of friendship between those who walk and their shoes. It is about walking, crossing paths, life paths. When what is everyday flatness is folded, it comes alive.

A lot of care was also given in designing Gary Chang’s My 32m2 Apartment – a 30-year transformation. It is light and in a horizontal grid, also flatness folded, not immediately hugging the body, but offering the home-dwelling safety and adventure at the same time. While explicitly autobiographical and documentative as a book that describes Chang’s apartment he had lived and transformed a large part of his life, it also exudes a strong sense of jumpy mischief, as if between the pages, a genie dances and plays hide and seek. Eric Wear suggests in his essay “Beyond compromise: a supple architecture for desires”, that Chang’s apartment opens like a book, or an accordion. Wear’s celebration of a book as an object designed to be a total world folding in, while ready to fan out its rhythm, is a tasteful one: firm and soft-spoken.

MCCM Creations is a small publisher based in Hong Kong. In November this year, it made the rare move of launching these three books in one go - rare, because Mary Chan who founded the publishing house has no appetite of personal fame; she had rather attribute attention and publicity to serendipity. “Never,” MCCM says in its book launch announcement, “have we thought three books would be released at once.” Rare also, because the very arrival of the three books was contemporary to the times when the form of the book itself is seriously questioned.

I am thinking of a forwarded email I (and perhaps many readers, too) received early this year calling for contribution to The Last Book project. It was sponsored by the National Library of Spain and curated by Luis Camnitzer. The curatorial statement says “the premise of the project is that book-based culture is coming to an end.” Hence, it sets out to “compile written as well as visual statements in which the authors may leave a legacy for future generations.” As I write, the curator has announced that the exhibition is scheduled to open on Nov 18, 2008. In Hong Kong, a contemporary art exhibition several months ago called *bōk- carries the sub-title “book review in this bookless age”.

How then, is the celebration of the arrival of new books to be understood? I remember a course on book design I was invited to co-teach. I was responsible for suggesting directions on the cultural and philosophical meanings of the book as a designed object. In the first class, I distributed to students lines from the dedication pages I copied from different books. My favourite ones include that of Paul Monette’s Becoming a Man – Half a Life Story. His dedication says, “For my brother who's walked the tallest of us all / And for Winston who keeps me dancing even in the dark.” Sadie Plant’s dedication was soulfully written, too. In zeros + ones, Digital Women + The New Technoculture, it says, “To all the contributory factors”.

I wanted these student designers to begin from treating the book as a gift that makes no demand on the benefactor for reciprocal returns. It is a gift from an elsewhere the reader never knows but is invited to appreciate as a guest with no obligations. I wanted them to notice faces of strangers always already inscribed in every book. Perhaps it is when the host disappears from what he/she has so hospitably hosted that his/ her skills are at their best, and the guests, the most at ease, the most comfortable.

When Fung says, “To my father, mother…and all parents,” and when Tsui says, “In memory of my grandmother Xie Zhan Yun, who taught me how to sew,” one finds any declaration of the first and the last quite irrelevant – each book is a home return to a vast world, dotted with silent voices that hew out the nuances of its many sides. I tend to think, as long as the world is recognized, books are not ready to die.

First published in Singapore Architect Issue 248, 2008.